Henry Beaufort, 3rd Duke of Somerset

Henry Beaufort was born on 26 January 1436, and was executed on 15 May 1464 following his capture in the aftermath of the Battle of Hexham. The eldest son born to Edmund Beaufort 2nd Duke of Somerset and his wife Eleanor Beauchamp. Closely related to the Lancastrian Royal Family and the House of York, he inherited his title aged 19, as a result of his father’s death in the First Battle of St. Albans. He was immediately a political ‘hot property’ given the nature of his father’s death and the prominence of the 2nd Duke of Somerset within the Royal Court.

Note: The Dukedom of Somerset was recreated for Henry’s father, so in technical terms Henry was 2nd Duke of the 2nd creation. He is popularly known as the 3rd Duke, albeit inaccurately, hence the use of that title for search engine purposes.

Henry Beaufort’s Inheritance

Henry Beaufort was the eldest son of Edmund Beaufort. He too fought in the First Battle of St. Albans and inherited the Dukedom of Somerset upon his father’s death in that clash. The Yorkist affinity were aware of the potential for the young duke to present them with political or military problems. To counter this, Henry was placed in the care of the Earl of Warwick. The adage of keeping ones friends close but your enemies closer did not prevent conflict for long.

A letter penned by John Gresham to John Paston on 16 October 1456 describes events that took place whilst the magnates of the land were in residence in Coventry for a Great Council. Men of the Duke of Somerset’s household caused a ‘great affray’ against the watch.

“On Moneday last passed was a gret affray at Coventre bytwene the Duke of Somersets men and the wechemen [watchmen] of the toun, and ij. or iij. men of the toun were kylled there, to gret disturbance of alle the Lords there; for the larom belle was ronge, and the toun arose, and wold have jouperdit to have distressed the Duke of Somerset, &c., ne had the Duke of Buks not have take a direccion therein[i]”.

The clashes appear to have been an attempt at asserting some authority over proceedings. It failed and required the intervention of the Duke of Buckingham to prevent the townsfolk targeting the Duke of Somerset. The same source informs us that there was ‘opynyon is contrary to the Whenes [Queen’s] entent, and many other also, as it is talked’. The Duke of Somerset, among others, were strengthening their ties to the Queen, factionalism was on the rise again.

Somerset versus York

French Threat

The enmity between the Dukes of Somerset and York and their affinities continued unabated throughout 1457. As 1458 began there was a large political divide, further complicated by a threat presented by the French. This threat was significant and impacting on trade.

“John Vyncent of Bentley was at the Priory of Lewes in Sussex this week, and says that sixty sail of Frenchmen were sailing before the coasts, keeping the sea. The Lord Fauconberg is at Hampton with his navy. Edmund Clere of the King’s house has heard from a soldier of Calais that Crowmer and Blakeney is much spoken of among Frenchmen. ‘The King’s safe conduct is not holden but broken, as it is voiced here, and that will do no good to merchants till it be amended.’ Figs and raisins are dear at 18s[ii]”.

That there were 60 French ships at sea was a significant risk. Even with a mixture of vessel types and sizes, a fleet of 60 ships is a greater fighting force than any of those deployed against the English coastline in the raids of the Hundred Years War. The potential for landing, raiding, and destroying ports or coastal communities was great. In August of 1457 a French flotilla had raided Sandwich, killed the mayor, and burnt much of the town. [Not to be confused with the 1460 Yorkist Raid on Sandwich].

Attempts to improve relations

With the French at sea, the magnates of England could not be allowed to be at loggerheads. For the sake of the country, they would need to be brought together. Sandwich had been so easily assaulted by the French, in part, because Council had been distracted by internal divisions. The fleet at Calais had not been paid, an ongoing concern but at this time an issue that was compounded by the Earl of Warwick being Captain of Calais and the ill feeling between the Earl and Duke of Somerset. These matters, and the need to deescalate tension between the factions, led to a series of agreements, bonds, and declarations that culminated in a Loveday Procession that was held at St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Bonds of Recognisance

On 23 March 1458 a series of bonds of recognisance were issued. Issued to the Dukes, Earls, Duchess and Countesses who had suffered or caused losses in the First Battle of St. Albans they saw bonds being required of each individual which would be held on,

‘Condition, that [s]he shall abide and obey the king’s award touching all controversies, trespasses, debts, debates, actions, offences, condemnations, executions and demands between him and [their opponents][iii]’.

The use of Bonds of recognisance was commonplace as a means of keeping the peace. Rarely, however, had they been issued to so many of the most senior magnates at the same time. These bonds would be lodged with the treasury with as a security for the future good conduct of the individual. Should they break the conditions, the bond would be lost. The amount lodged as a bond was therefore a considerable sum, based upon the wealth of each individual.

Loveday Procession

Holding the lords to bonds of recognisance was not on its own enough though. There needed to be public awareness of the promises made by these powerful overlords and influential ladies. This was achieved through a Loveday Procession.

“Item the xxiiij day of March our lady Eve of Annunciacion the king and quene being at Westminster and divers lordes condescended and agreed and ther made a full unyte and peas betwene the dukes of york and somerset and betwene the Erles Warrewyk Salesbury Northumbrelond and lord Clifford: ^ and the king pardoned all things doon afore aswell at Seint Albons as elles wher and proclamacion made peroi the same day thurgh the citee and therupon on the morn the King and Quene and the lordes yede a procession at powles (which ^) was a greet gladnes and comfort to the peple[iv]”.

The Duke of Somerset and the Rise of Violence

The Loveday and bonds of recognisances did little to alter the animosity between the Duke of Somerset and his adversaries. 1458 saw the Earl of Warwick set upon. April of 1459 then saw a fatal clash on Fleet Street between men loyal to the two factions[v]. The Queen and her adherents moved Court to Coventry and there was a marked increase in the issuing of the Prince of Wales’ livery. A Great Council was called in June that the Yorkists refused to attend. Soon the plans of the Court party were made clear.

As both factions arrayed forces it was clear that the Yorkists would need to converge in order for them to present a strong enough front. This could be countered by the Court party as they commanded lands through which the Earls of Salisbury and Warwick would need to march if they were to join with the Duke of York.

Blore Heath, Ludford Bridge and the Ascendancy of Henry Beaufort and the Court Party

The Duke of Somerset had a force at his disposal that was arrayed to the north west of Coventry[vi]. It was ideally placed to intercept the Earl of Warwick as he marched towards Ludlow. On 21 September 1459, the Earl’s force passed the Duke of Somerset’s positions unhindered. Two days later Baron Audley ambushed the Earl of Salisbury’s army at Blore Heath. The intention to prevent the Yorkists combining their force seems clear. The reasons for the Duke of Somerset having not engaged the Earl of Warwick are unclear.

The Yorkists had managed to unite their forces, the Earl of Salisbury having been victorious at Blore Heath. They were based at Ludlow. The Court Party, with the King present, marched toward the Yorkists. This presented the Duke of York and his affinity with a dilemma. They could not claim to be loyal to the king if they fought against him. Nor could they simply submit as their enemies within the Court party would almost certainly have them arrested on charges of treason. The outcome was the rout at Ludford. The Yorkists fled once the Calais contingent led by Sir Andrew Trollope had defected to the royal army.

Parliament of Devils: Duke of Somerset granted roles

Following the flight of the Yorkists the Court Party held Parliament in Coventry and attainted the Yorkist leaders. The Duke of Somerset as a leading magnate of the faction was a beneficiary of the reallocation of roles. The Captaincy of Calais was nominally granted to the duke. He would, however, need to take possession of the port city by force as it remained loyal to the Earl of Warwick.

The appointment as Captain of Calais was one that the duke attempted to take up almost immediately. Taking Calais would be a hammer blow to Yorkist hopes of a revival and was specifically aimed at the subject of Henry Beaufort’s hatred, the Earl of Warwick. The duke’s attempt to take possession was a failure. He,

“with a certeyne nombre of men of armes, hauyng with theym the kynges letters, wente to Caleys to thentent that the seyde duk shulde haue be cap- teyne of Caleys… they of Caleys wolde haue take hym, and with muche payne he escaped and fled in to the castelle of Guynes…[vii]”

Duke of Somerset’s attempts to seize Calais

Attempting to take the Port of Calais from sea had failed. He now attempted to take it by land. This required reinforcements. This too proved to be a failure. Not only did the Earl of Warwick hear of the plans, he managed to sail across the English Channel, attack the fleet in the haven of Sandwich, and capture Earl Rivers, sink several ships, and take possession of others. The Duke of Somerset’s siege continued through the winter into spring of 1460.

Two events in April 1460 brought the Duke of Somerset’s attempts to seize Calais to an abrupt and embarrassing end. First,

“the duk of Excestre, that was Amyralle, was sent to the see with a grete nauy for to dystresse the seyde erle of Warrewyk and his nauey, and sayled from Sandwyche to Dertemouthe, and there for lack of vetayle and of money hys soudyers were dysparbeled, and wente awey fro hym.[viii]”

The Yorkists had managed to gain naval superiority in the Straights of Dover and English Channel. The Duke of Exeter, Admiral of the Fleet, was forced to remove the remaining ships from Sandwich as there was insufficient funds to pay the crews, and the haven was proven to be insecure.

Second, the failure of a frontal assault on Calais. Knowing that he had limited resources and time in which he could now take the port, Henry Beaufort opted to attempt to seize the entry to Calais. This desperate attempt was fended off by the garrison and the Duke was forced to return to England without having had any success against the main fortifications at the Port of Calais.

Henry Beaufort’s failure at Calais

There were major political consequences of the failure to oust the Yorkists from Calais. The Earl of Warwick was able to sail to Ireland to meet with the Duke of York. Lancastrian shipping and forces were attacked on more than one occasion. Yorkist support in the south-east was made aware of plans. And in June 1460, the Yorkists were able to sail from Calais to Sandwich, take the town, and march on London. The Court Party had seen its dominance shattered, and following the Battle of Northampton on 10 July 1460, it was they who found parliament being used against them. As the Yorkists pulled off this extraordinary turn around in their fortunes, the Duke of Somerset had been based in the castle at Guisnes in the Pale of Calais, unable to intervene.

Henry Beaufort stranded in France as the Yorkists dominate

For the Duke of Somerset, the series of events led to him leaving Guisnes for the safety of France. Henry Beaufort was therefore in France as the Yorkists consolidated their hold on power. So too was he overseas as Richard 3rd Duke of York returned, claiming the throne for himself. The outcome, the Act of Accord, was a compromise that suited nobody in the short term. Least of all those like Henry Beaufort whose rank, income, and roles were all due to his families ongoing patronage from the House of Lancaster.

Potential consequences of the Act of Accord for the Duke of Somerset

The Duke of Somerset, and others in the affinity of Queen Margaret and Prince Edward, now faced a dilemma. If the Act of Accord were to remain, the bond to the Queen would weaken over time, then, with the accession of a Yorkist, be either broken or relatively worthless. Magnates such as the Duke of Somerset who had been proactive in seeking the attainting of the Yorkists would almost certainly lose their status, and possibly life, if the Act of Accord was to take effect. The system of patronage had benefitted the Beaufort family greatly. They had risen to the highest echelons of Government and Church. Patronage from each of the Lancastrian kings had bound them firmly to family now effectively headed by Queen Margaret on behalf of King Henry VI and Prince Edward. Bound by patronage, forced by circumstance, the Duke of Somerset and others of the Queen’s affinity chose to combat the Act of Accord through force of arms.

Duke of Somerset in Dieppe

The consequences of the Yorkist revival were clear to the Duke of Somerset and others in the Queen’s affinity. A letter dated 12 October 1460 from Christopher Hansson to John Paston notes that:

“As for tythyngs here, the Kyng is way at Eltham and at Grenewych to hunt and to sport hym there, bydyng the Parlement, and the Quene and the Prynce byth in Walys alway. And is with hir the Duc of Excestre and other, with a fewe mayne, as men seythe here.

…the Duc of Somerset he is in Depe [Dieppe]; withe hym Maister John Ormound, Wyttyngham, Andrew Trollyp, and other dyvers of the garyson of Gyanys, under the Kyng of Fraunce safcondyte, and they seythe here, he porpose hym to go to Walys to the Quene. And the Erle of Wyltschyre is stylle in pece at Otryght at the Frerys [Friars], whiche is seyntwary[ix]”.

In the same way that the Yorkists had chosen to avoid Great Council and Parliamentary sessions, so too had the Court party chosen to do so in October of 1460. As the Yorkists had done, the leaders had separated, in the case of the Duke of Somerset to Dieppe, others to Wales, and the Earl of Wiltshire into Sanctuary.

Bales chronicle notes of the actions that nobles including the Dukes of Somerset and Exeter who, “wer sett of affnite and purposed as was reported and seid to have doon greet myschief and hurtes as they afore had used undre counciles and colour of supporting the kings right which proved evermore contrary as shewed be their werke[x]”. The bond of affinity to the faction led by the Queen had, therefore, held firm after the Act of Accord was passed. Despite the Act being a compromise in Council and, it having been granted royal assent by King Henry VI, the faction continued to be ‘supporting the kings right’ and that of what they perceived to be the true heir to the throne, Prince Edward. In simple terms, those in the affinity of the Queen and Prince Edward continued to support the prince and remained true to each other as a faction.

Lancastrian Fightback: led by Henry 3rd Duke of Somerset?

At Wakefield on 30 December 1460, a Lancastrian army that defeated the Duke of York’s force. The Duke of York was killed in the battle. His son, the Earl of Rutland, was killed in or shortly after the battle. The Earl of Salisbury was taken prisoner, then beheaded at Pontefract Castle. The death of leading Lancastrians, including the Duke of Somerset’s father five years earlier, had been avenged. It is not entirely clear (yet) where Henry Beaufort 3rd Duke of Somerset was on 30 December 1460. Some sources suggest he was one of the commanders at Wakefield, whereas others have him arriving in the north in 1461. Either way, he was part of the inner circle of the Queen and would have had some input in any strategic thinking following the Act of Accord, albeit it from a distance at times.

Henry Beaufort Commands at St. Albans (1461)

This was the beginning of a series of battles that would determine the kingship of England for the next decade. Following the victory at Wakefield the Duke of Somerset went to York. From here the Lancastrian army, with Queen Margaret now present, marched south. The objective was to take London, recover King Henry VI from the Yorkists, and deal with the Earl of Warwick and other Yorkists in a decisive manner. The advance saw the Duke of Somerset command at the Second Battle of St. Albans. Here, the prize of King Henry was won, as the Yorkists left the king behind as they fled from the field, having been outwitted in battle.

Victory at St. Albans was not decisive. The Earl of Warwick had retreated to London, and the Duke of York’s heir, Edward, had defeated a Lancastrian force at Mortimer’s Cross. There was now a large Lancastrian army, with the Dukes of Somerset and Exeter as the battlefield commanders, approaching London. The Yorkists had the remnants of the Earl of Warwick’s force, and that of Edward Earl of March. London was the prize for both. The Yorkists gained the upper hand as the City of London refused Queen Margaret’s army, or her representatives, entry to the city. In the meantime, the Yorkists had declared Edward to now be the legitimate king of England.

Edward Earl of March proclaimed King

England now had King Henry VI, an anointed king who was with lords loyal to him and to Prince Edward’s birthright. It also had King Edward IV. Edward’s claim was based on the principle that in joining the Queen and Prince Edward on the field of battle at St. Albans, King Henry VI had broken the Act of Accord. According to the Yorkist argument when his kingship was ratified, this was justification for immediately enacting the inheritance of the throne as the Act had stated it would upon the death of King Henry VI[xi]. It was in essence a political power play by the Yorkists to gain additional support through an argument of legitimacy.

The matter of kingship aside, the Act of Accord had been ignored by a series of nobles, including the Duke of Somerset. The Act had been passed by Parliament and was English law. The lords in the affinity of the Queen were loyal to the crown but not to parliamentary process and state processes. In this scenario each noble was at odds with the norms of loyalties. The nature of what was now a civil war made it impossible for those in the Court party to retain bonds to both Lancastrian kingship and the Parliamentary process. To work with one would mean exclusion from the other, as had been the case for the Yorkists in exile.

Lancastrians in the North

When the Lancastrians found themselves denied access to the City of London they chose to retire to the north, returning to York. The City of York, despite the dukedom in its name, was largely surrounded by estates of nobles who were adherents of Queen Margaret. The Yorkists, when they chose to march north to face the Lancastrians, would be faced with fierce resistance at the crossing points of the River Aire, need to pass through lands that were loyal to the Queen, pass close to Castles that were held by men of the Queen’s affinity. And would be doing so after provisions had been acquired by the retreating army of the Lancastrians. Furthermore, there was hope that agreements could be made with the Scots, should the talks of Christmas 1460 be progressed. Strategically there was much logic in the decision to head north, a choice that must have been at least in part been influenced by senior commanders such as Henry Beaufort.

That there would be a major clash between the two sides was inevitable. Both factions stood to lose everything if they did not resolve matters in a decisive manner. Neither side would be willing to trust the other and the chivalric expectation of a noble being taken prisoner and held securely until a ransom was paid had been put to one side at Wakefield, so mercy could not be expected by either side. It had become a ‘do or die’ situation for the leading magnates.

Battle of Towton

The expectation of crushing the Yorkists in battle must have been high. Far superior in numbers and on a field of their own choosing, the Duke of Somerset would have been confident that the army under his battlefield command would prevail. It was not to be, after a bloody battle to take control of Ferrybridge the Yorkists had advanced north of the Aire. The Battle of Towton that followed on Palm Sunday 1461 was said to be long and bloody. Eventually the Yorkist force, bolstered by the arrival of fresh soldiers under the command of the Duke of Norfolk, seized the initiative. Hearne’s Fragment summarises the traditional version of events succinctly:

“This field was sore fought. For there were slain on both parts 33,000[xii] men, and all the season it snowed. There were slain the Earls of Northumberland and Westmorland with others and Sir Andrew Troloppe; and taken the Earls of Devonshire and Wiltshire and beheaded there; The Earls of and the deposed King Harry, his Queen, with Henry, Duke of Somerset, and others, in great haste fled into Scotland[xiii]”.

Flight to the North

As it became clear that the day was lost, the Duke escaped the field of battle and made his way to York. From here he, in the company of King Henry VI, Queen Margaret, and a number from the royal household, made their way to the safety of Scotland. This was simply the best option for the senior members of the Lancastrian leadership. Those who could, escaped to fight another day. In Scotland they were assured of a reasonably warm and secure welcome.

Exile in Scotland also provided an opportunity for the Queen to communicate with her French relatives. Now was an opportunity for the Lancastrians in exile to make use of the Auld Alliance as best they could. The Paston Letters includes correspondence from Lord Hungerford and Robert Whittingham[xiv] to Queen Margaret that notes the Duke of Somerset had travelled to Dieppe by August 1461, whilst the Royal family remained in Scotland with a small but notable group of their supporters. Henry Beaufort was still in France in October, being noted in correspondence[xv] as being near Calais whilst other leading Lancastrians were engaged in actions in Wales and Scotland. The Duke of Somerset was clearly a leading figure in the coordination of the attempts to regain the initiative against the Yorkists.

Loyalties, Responsibilities, and Rights

This period illustrates the various ways in which the matters of loyalty, responsibility, rights, and honour were viewed by the leaders of both the Lancastrian and Yorkist factions. Both sides had summarily executed captured nobles in 1460/61. There had been defections either in the face of battle, or during the fighting itself. Acts of Parliament and attainders had been ignored or overturned. Yet there was still some semblance of honorable behaviour. Whilst Henry Beaufort was working with Queen Margaret and others such as the Duke of Exeter and Jasper Tudor to keep the Lancastrian cause alive, Edward IV issued an, “Order to pay to Margaret duchess of Somerset 166l. 13s. 4d. a year for life; as the king has learned how that she holds that yearly sum for life by endowment of John duke of Somerset her husband and assignment of the late king as dower of an annuity of 500l. of the said custom[xvi]”. A grant that was respectful of the awards of King Henry VI’s reign and that was reiterated in further orders whilst her son was still preparing to wage war against Edward IV[xvii].

Henry Beaufort in Scotland, 1462

By March of 1462 the Duke of Somerset had returned to Scotland[xviii]. The period was one of frenetic diplomacy by both sides. The Lancastrians following up the duke’s talks in France with a visit by Margaret of Anjou herself, which resulted in French money and aid being promised. At the same time the Yorkist regime was busy making secret pacts with John of Islay, Earl of Ross, Lord of the Isles which was designed to undermine King James III. The fluidity of the situation meant that coordinated assaults against the Yorkist regime were hard to achieve. In autumn of 1462 though there was a break through of sorts for the Lancastrians.

Bamburgh

Queen Margaret had obtained the use of forty two ships under the command of Pierre de Brézé. This fleet put to sea with a thousand French soldiers and made for North East England. The Duke of Somerset also set sail, from Scotland, and landed at Bamburgh with a force of exiles and Scots. With the area having been part of the Earl of Northumberland’s lands, it was hoped that the locals would rise against the Yorkists in support of the invading force. That wasn’t to be, but the garrisons at several of the North Eastern sea facing castles did declare their loyalty to King Henry VI whilst others soon fell to the Lancastrian force.

The result was a fortified enclave in the North East that ensured that King Henry ruled over at least a portion of his domain. To survive, these castles needed supplies and more men from Scotland. Queen Margaret heading north to arrange this, the Duke of Somerset remained to take charge of Bamburgh Castle.

The response of the Yorkists to the return of Lancastrian forces in the North East was swift. We learn from a letter from John Paston Junior to his father that by 1 November, “my Lord of Warwyk yed forward in to Scotland as on saturday last past with xx.ml. [20,000] men; and Syr Wylliam Tunstale is tak with the garyson of Bamborowth, and is lyke to be hedyd, and by the menys of Sir Rychard Tunstale is owne brodyr[xix]”.

Duke of Somerset Surrenders to the Earl of Warwick at Bamburgh

Militarily the defenders of Bamburgh could realistically only hold out if they were supplied and reinforced by sea. The Earl of Warwick had a large army and had large calibre cannon available. The duty of the Duke of Somerset was to hold the castle for as long as was possible, to wait and hope for reinforcement, or for a discreet opportunity for escape being provided by his Scottish and French allies. Attitudes of the day looked unfavourably on men who surrendered. Henry Beaufort only needed to look at the way in which his own predecessors had been viewed when surrendering or failing to follow orders properly. The latter had seen the dukedom degraded to an earldom; the former had seen widespread derision. As a simple matter of honour, as a chivalric norm, as a military approach, the only acceptable course of action was for the Duke of Somerset and his men to hold Bamburgh Castle for as long as possible. Furthermore, was the personal aspect. The Duke of Somerset had actively attempted to oust the Earl of Warwick from his position at Calais, had contributed to the increased animosity between the two factions, had been in overall command when the Earl of Salisbury and Earl of Rutland were executed, or butchered. Anything other than fighting to the bitter end would be unacceptable and humiliating. Yet the Duke of Somerset chose to take the Earl of Warwick at his word on a promise of pardon in return for his surrender.

Hearne’s Fragment paints a slightly different picture. In this account the taking of Bamburgh was accidental, as the ship was forced ashore there by inclement weather. Nonetheless, the Duke and Sir Ralph Percy made little attempt at escaping, going as far as suggesting that the men had sought no remedy to escape. In burning their own ships, the Lancastrian lords were eliminating the possibility of a tactical withdrawal and placing themselves at the mercy of the Earl of Warwick[xx].

What we have then is a surrender on terms. The questions surrounding accepting these terms are whether or not the terms were accepted after sufficient attempts to withhold assault, whether the Queen and Lancastrian affinity stood to gain from prolonged resistance, and whether or not there was ever any intention on the part of the Duke of Somerset to adhere to the terms of the pardon.

Henry Beaufort 3rd Duke of Somerset in the Yorkist Court

What is clear is that despite the adoption of a no mercy policy in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Towton, both King Edward IV and the Earl of Warwick were now willing to countenance the granting of a pardon to the man who had commanded the Lancastrian army in the field and been central to the Court parties ongoing feuds with the Yorkists. It is an extraordinary turn around by both sides. The Yorkist change of heart is explained by the news that a relief force was heading to the North East from Scotland, that there was unrest and the last vestiges of resistance in Wales, and that King Edward was unwell with measles. In short, they wanted a fast resolution so that other matters could be addressed. The acceptance of the terms by the Duke of Somerset was after 6 weeks of defence. Enough time to dismiss charges of having simply given up. It was also in the face of a more concerted siege effort by the Yorkists who had not only moved ordnance into position. Not knowing that a relief force was en route, the fate of the castle may have seemed to be inevitable. In which case, the duke’s acceptance of a pardon may be viewed as being somewhat more honourable.

The Duke of Somerset attended court following his submission to the Earl of Warwick and receipt of his pardon from the king. Naturally, his presence was a moot point amongst the Yorkist affinity, who did not trust him and in many cases had suffered losses because of his actions as a member of the Queen’s affinity. This put a strain on the king’s policy of rapprochement. Whilst it is a responsibility of those in power to wield it for the greater good, it ought perhaps not be extended to forgiveness of all sins and favour being granted to those who had done nought to deserve it.

Henry Beaufort moves to Wales, then flees to Scotland

After some time, it became clear that the presence of the duke at court was likely to provoke incidents rather than lead to wounds being healed. Consequently, the Duke of Somerset was moved, with his pardon wholly intact, into a safer location in Wales. Here, some aspects of the terms of the surrender and pardon seem to have become unstuck. The Duke had been ‘in to King Edwardes grace, by whiche graunted to hym a [thousand] marke by yere, whereof he was not payde.’ The Duke ‘therefore departed oute of England after halfe yere into Scotlonde.[xxi]’

1463: Duke of Somerset and plots against the Yorkists

Whilst the Warkworth Chronicle suggests that it was the non-payment of the thousand marks per year annuity that led to the Duke of Somerset absconding and making his way north, the reality is that he had been plotting with his Lancastrian kin. An uprising in the Newcastle area began, and failed, as the duke made his escape[xxii]. That the duke had been conspiring is supported by a reference in a letter from John Paston the Youngest to John Paston Senior, that noted that, “my Lord hathe gret labore and cost here in Walys for to take dyvers gentyllmen here whyche wer consentyng and helpyng on to the Duke of Somersettys goyng; and they were apelyd of othyr se[r]teyn poyntys of treson, and thys mater” and that, “The Comenys in Lancasher and Chescher wer up to the nombyr of a x. ml. [10,000] or more[xxiii]”. The suggestion is that people were being arrested for having aided the Duke of Somerset in his treasonable return to the Lancastrian fold, and that some ten thousand men had risen in Lancashire and Cheshire in 1463.

See: Lancastrian forces in the North East and Treason: Aiding the Duke of Somerset’s return to the Lancastrian Fold

Battle of Hedgeley Moor

The Duke of Somerset made his way to Scotland and then into North Eastern England. In his absence the Scots had invaded in support of the Lancastrians. This force had been pushed back over the border but there remained a loyal band of Lancastrians who were willing to fight under the Duke of Somerset’s command. In April 1464 the Lancastrians attempted to ambush John Neville, Lord Montagu as he marched north to escort a Scottish delegation from the border to York. The first attempt failed, before the Lancastrians were able to cut off the route north on Hedgeley Moor. On 25 April the two sides clashed. The Lancastrian force quickly faltered, with many fleeing the battlefield when the extent of Lord Montagu’s force was realised. Henry Beaufort was among those who escaped, with a rear-guard of Sir Ralph Percy and his retainers being cut down by the Yorkist force.

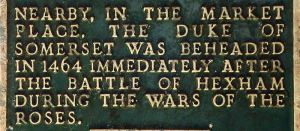

Battle of Hexham and the execution of Henry Beaufort 3rd Duke of Somerset

The Yorkist force was now intent of tracking down the Lancastrians and putting an end to the persistent threat that they posed in the region. On the night of 12/13 May 1464 Montagu’s army crossed the Tyne. On 14 May it marched towards Hexham where the Lancastrian force was encamped. The following day saw a rapid Yorkist advance on the Duke of Somerset’s encampment. The speed of the assault took the defenders by surprise leading to the encounter being a chaotic rout. During the clash at Hexham the Duke of Somerset and other leading Lancastrians were captured by Montagu’s men. They were taken into Hexham and that same evening the Duke of Somerset was beheaded. Further executions followed, leaving the Lancastrians leaderless in the region.

Postscript: Henry Beaufort posthumously attainted

Henry Beaufort had been summarily executed for having reneged on the terms of his surrender. Lord Montagu was unwilling to allow the duke another chance. His demise then was for the Lancastrian cause for which he had been a leading protagonist since his father’s death. It was not a glorious end but one at the hand of a hastily found axeman. In his time as duke, Henry had shown a steadfast resolve, at times, to seek retribution for his personal loss. Yet had then set aside honour and surrendered to the very man whom he held most responsible for the crimes against his family. If it was a calculated gamble to enable him to fight another day, it was of limited success. Instead, his presence in the North East resulted in a bolstering of Yorkist resolve to destroy Lancastrian resistance, in which he himself was captured and executed. The days that followed his defeat at Hexham saw all remaining castles that were in Lancastrian hands submit to Yorkist nobles.

Henry Beaufort was then posthumously attainted with his estates becoming crown property and the dukedom of Somerset in abeyance. The title was claimed, in exile, by Henry’s brother, Edmund. Edmund was in exile in France where he remained until the readeption.

Henry Beaufort: References

[i] Gairdner, James. Paston Letters (Volume 3) Letter 348.

[ii] Gairdner, James. Paston Letters (Volume 3) Letter 365.

[iii] ‘Close Rolls, Henry VI: March 1458’, in Calendar of Close Rolls, Henry VI: Volume 6, 1454-1461, ed. C T Flower (London, 1947), pp. 292-295. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-close-rolls/hen6/vol6/pp292-295 [accessed 30 June 2022].

[iv] Flenley, Ralph [ed]. Bale’s Chronicle. In, Six Town Chronicles. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1911.

[v] Moorhouse, Dan. On this Day in the Wars of the Roses, 2021. Page 113.

[vi] Amin, Nathen. The House of Beaufort: The Bastard Line that captured the crown. Amberley, 2017. Page 246.

[vii] Davies, Rev. John Silvester (ed). An English Chronicle. Page 84.

[viii] Davies, Rev. John Silvester (ed). An English Chronicle. Page 85.

[ix] Gairdner, james. Paston Letters (Volume 3) Letter 419.

[x] Flenley, Ralph (ed). Bales Chronicle, in Six Town Chronicles. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1911. Page 152.

[xi] Kleineke, Hannes. A New Dawn? The accession of Edward IV on 4 March 1461. History of Parliament Commons 1461-1504 project. https://thehistoryofparliament.wordpress.com/2021/03/04/a-new-dawn-the-accession-of-edward-iv-on-4-march-1461/ Accessed 02/07/2002.

[xii] Contemporary and near contemporary accounts provide a wide range of casualty figures. As such they should not be taken as being reliable. Modern interpretations suggest that whilst the battle was clearly large, casualty figures were most probably far lower than suggested in Hearne’s Fragment.

[xiii] Hearne’s Fragment, Chapter 3

[xiv] Gairdner, James. Paston Letters (Volume 3) Letter 480

[xv] Gairdner, James. Paston Letters (Volume 3) Letter 483

[xvi] ‘Close Rolls, Edward IV: July 1461’, in Calendar of Close Rolls, Edward IV: Volume 1, 1461-1468, ed. W H B Bird and K H Ledward (London, 1949), pp. 7-16. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-close-rolls/edw4/vol1/pp7-16 [accessed 4 July 2022].

[xvii] ‘Close Rolls, Edward IV: 1461’, in Calendar of Close Rolls, Edward IV: Volume 1, 1461-1468, ed. W H B Bird and K H Ledward (London, 1949), pp. 26-31. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-close-rolls/edw4/vol1/pp26-31 [accessed 4 July 2022].

[xviii] Gairdner, James. Paston Letters (Volume 4) Letter 512

[xix] Gairdner, James. Paston Letters (Volume 4) Letter 532

[xx] Hearne’s Fragment, Chapter 8.

[xxi] Warkworth’s Chronicle, page 3.

[xxii] Bicheno, Hugh. Blood Royal: The Wars of Lancaster and York, 1462–1485. Head of Zeus, 2016. EBook, Chapter 2: Warwick.

[xxiii] Gairdner, James (ed). Paston Letters (Volume 4). Letter 560