The king was placed under a tree… where he laughed and sang

News of the events at St. Albans on 17 February and the aftermath in London did not always reach the continent quickly, or accurately. This letter from the Milanese ambassador to Court of France illustrates the events. It adds some detail to earlier accounts, such as the locations of various parties and an indication of the course of the battle. It is though perhaps most notable for it’s inclusion of detail that is questionable at best in it’s accuracy: namely the numbers involved, and the manner in which King Henry VI was found by his Lancastrian kin.

Course of the Battle

On statistics, this letter is staggering. The Queen‘s army having ‘quite 120,000 of whom went away for lack of victuals’ and a mounted division of the ‘Duke of Somerset after midday came with 30,000 horse’. He goes on to say, ‘Accordingly with 4,000 men he [Somerset] pushed through right into Albano, where the queen was with 30,000 men‘. Ignoring the numbers that are suggested, the battle is said to have seen horse under the Duke of Somerset assault the Yorkist positions, with the Queen having a force in St. Albans. At which, the Earl of Warwick feared treason and fled the scene.

King Henry VI after the flight of the Yorkists

The king was placed under a tree a mile away, where he laughed and sang

The accuracy of this is impossible to ascertain, though it was clearly based upon words uttered somewhere in England. It is followed by the statement that the two ‘princes’ [lords] who had remained at the King’s side were not treated mercifully:

on the morrow one of the two detained, upon his assurance, was beheaded and the other imprisoned

Yorkist response to St. Albans

Prospero di Camulio is writing this after news of the proclamation of Edward IV as King reached him. The Yorkists had, according to Camulio, amassed an army of some 200,000, or 150,000 in the days after St. Albans. The people of London are said to be supportive of the Yorkist cause: which is at odds with other Milanese letters which illustrate that the City of London negotiated with Queen Margaret in the days between the battle at St. Albans and the writing of this letter. Notwithstanding the contradictions within the letter, he notes that:

The rest of the princes and people, full of indignation, made my lord of March king

Furthermore, the Lancastrian response to this was a swift political decision. Though wrong, the Milanese at the time believed that:

Accordingly the queen and the Duke of Somerset, in desperation, had persuaded the king to resign the Crown to his son, and so he did out of his good nature.

Lancastrian retreat to York

With an element of acceptance that his figures are somewhat fantastical, Camulio notes that England is now fully armed:

My Lord, I am ashamed to speak of so many thousands, which resemble the figures of bakers, yet every one affirms that on that day there were 300,000 men under arms, and indeed the whole of England was stirred, so that some even speak of larger numbers.

And without noting that the Queen’s army had threatened London, recounts how the Lancastrian force then heded north, to the City of York:

the queen, her son and the duke withdrew to York, a strong part of the island towards the North

Prospero di Camulio, Milanese Ambassador to the Court of France, etc., to Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan.

71. Prospero di Camulio, Milanese Ambassador to the Court of France, etc., to Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan.

We hear many strange things from England day by day and hour by hour. A letter written to the Dauphin by one who was at the great battle on Shrove Tuesday gives full particulars of the princes, the numbers engaged, the assaults, the blows, the wounded and the rumours circulating that day on one side and the other. It is to the effect that on that day the king’s men were encamped ten miles away at a place called Albano; quite 120,000 of whom went away for lack of victuals, no small number (ben cxxm de li quali se ne partisse per diffecto de vectuali anon puochi). The Duke of Somerset after midday came with 30,000 horse to scent out the Earl of Warwick and the king’s forces and wore them down with his attack, and the Earl of Warwick decided to quit the field, and to break through against them. Accordingly with 4,000 men he pushed through right into Albano, where the queen was with 30,000 men. The earl, seeing himself alone and the day far spent, returned to the camp, closely pressed by the followers of Somerset; and when he reached the camp he heard some shouting from his camp to the enemy. Fearing some act of treason, he got away as best he could (Lo Duca de Sambreset post meridiem venne cum cavalli xxxm ad anasare lo conte de Varuich et la gente del Rey et li fecero assai lasso l’assalto et lo conte de Varuich se delibero de usir del campo et erumpere contra loro, et cossi cum ivm homini lo casso fin dentro Albano unde era la regina cum homini xxxm et lo conte videndosi solo et lo di basso, se ne ritorno al campo sempre hortato et cassato da li Sambreseti et quando fu al campo intese de quello se vociferava dal campo suo a li inimici et dubito ymo vedette acti de tradimenti et se parti meglio che l’possette).

The king was placed under a tree a mile away, where he laughed and sang, and when the defeat of the Earl of Warwick was reported, he detained upon his promise the two princes who had been left to guard him. Very soon the Duke of Somerset and the conquerors arrived to salute him, and he received them in friendly fashion and went with them to St. Albans to the queen, and on the morrow one of the two detained, upon his assurance, was beheaded and the other imprisoned (lo rei era posto longi de li uno miglo sutto uno arboro unde se rideva et cantava et essendo voce de la rupta del conte de Varruich, ritenne supra sua fede li doi Principi che gli eran stati lassati a la guardia. Assai tosto vennero lo Ducha de Sambrecet et li vencitori a salutarlo; a quali el fece bon volto et se ne ando cum loro ad Albano a la Regina et l’undomani uno de li doi ritenuti in fede sua fu decapitato, l’altro incarcerato).

That day some 4,500 men perished, in one skirmish and another, lasting from midday until midnight.

The earl betook himself to my lord of March and they at once collected quite 200,000 men, and it seemed that victory would rest with the side that London favoured (lo Conte se retaxe cum Monsignor de la Marcha et subito recolsero ben homini ccm et restava la cosa in tal contrapeso che pareva unde Londres inclinasse, li esser la victoria).

Subsequently, by letters which arrived yesterday, also for the Dauphin, we learn from a most honest person, how my lord of March and the Earl of Warwick had quite 150,000 men, the finest troops ever seen in England, and, owing to some not over legitimate actions of the king and his party, London inclined to my lord of March and the Earl of Warwick. Accordingly the queen and the Duke of Somerset, in desperation, had persuaded the king to resign the Crown to his son, and so he did out of his good nature. That done, they left him, and the queen, her son and the duke withdrew to York, a strong part of the island towards the North (per alcuni acti non ben legitimi del Rei et de la banda sua, inclinava Londres verso Monsig. de la Marcha et lo dicto Conte de Varruich et Cossi desperata la regina et lo Ducha de Sambrecet havian persuaso lo Rei a deponer la corona in lo figlolo et cossi fece per sua bonta. Quo facto, lo han lassiato et se son retracti la Reina, lo figlolo et lo Ducha in Horch, chi e una parte paese forte de la Insula, verso tramontana).

The rest of the princes and people, full of indignation, made my lord of March king. We have this by several letters worthy of credit, but, being a matter of such very great importance, it is not fully credited, though we expect fresh news in two or three days.

My Lord, I am ashamed to speak of so many thousands, which resemble the figures of bakers, yet every one affirms that on that day there were 300,000 men under arms, and indeed the whole of England was stirred, so that some even speak of larger numbers. If this be so it might be better for me to cross when matters are more settled, to visit and congratulate him as I was to visit and congratulate his late father; but I will abide by what your Lordship directs. I would remind you, if you please, that it will be necessary for me to have fresh letters of credence, etc.

Within four days I shall be with the Duke of Burgundy, if God wills, to visit him and maintain his friendship with your Lordship, but I do not think it advisable to say anything to him about the difficulty about the league with the Dauphin, since the matter is reduced to…. I commend myself to your Excellency.

Ghent (Genepie) the 9th of March, 1461.

[Italian; the part in italics deciphered.]‘Milan: 1461’, in Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts in the Archives and Collections of Milan 1385-1618, ed. Allen B Hinds (London, 1912), British History Online

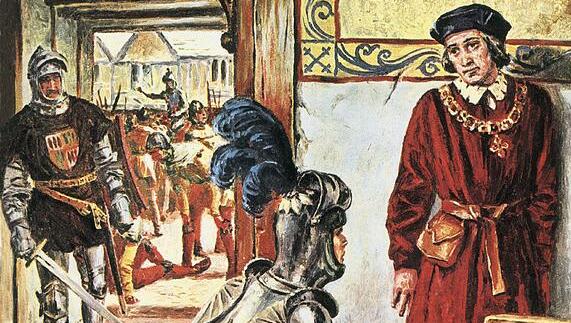

Image Credit

Henry VI — The King Who Was Too Kind. From A Pageant of Kings. Artist CL Doughy.