Trial by Combat

Trial by Combat is a form of legal process that is typically associated with the earlier parts of the medieval era. It was, however, still an option within the period of the Wars of the Roses. Whilst rarely used, it was on occasion. In the case below it was the chosen mode of determining the innocence or guilt of an alleged thief, a Thomas Whytehorne. The defendant was from Mylbroke [Millbrook] near Southampton. He was arrested and taken into the King’s custody whilst in the New Forest, near Beaulieu Abbey. His case was heard in Winchester and was recorded in Gregory’s Chronicle, suggesting that it was considered quite peculiar at the time.

The following case took place in the reign of King Henry VI. It is noted in Gregory’s Chronicle after the First Battle of St. Albans. Such trials were far from being commonplace by the mid 1450’s. Justice would more usually be administered via hearings at local, regional, or national level by Justices of the Peace, the Lords, or Council. Exeptions to this are evident throughout the Wars of the Roses but these tend to be instances in which a treason, or perceived treason, was tried. These instances were usually overseen by the Constable of England, such as the trials of the Earl of Oxford, or those that took place following the Battle of Tewkesbury.

The allegation

Thomas Whytehorne was accused of stealing. This took place within the New Forest, close to the monastic community at Beualieu Abbey. As such the alleged offence took place within the confines of the Royal Forest and was subject to Forest Law.

Whytehorne pleaded his innocence and begged for his life. In his assertions he said that he would defend his innocence, and would do so by ‘preve hyt with hys hondys’. The Chronicle also notes that others had been ‘honggyd’ and ‘hadde noo frende shyppe and goode’. In short, Whytehorne was offering to be subjected to Trial by Combat, knowing that others had been hanged for similar accusations and hoping to ‘prove’ his innocence via this method of justice.

The Trial by Combat

The suggestion was considered, then accepted.

And a notabylle man, and the moste petefullyste juge of al thys londe in syttyng a-pon lyffe and dethe, toke thys sympylle man that offeryd to fyght with the peler, ande fulle curtesly informyd hym of alle the condyscyons of the fyghtyng and duelle of repreffe that shulde be by-twyne a peler of the kyngys, fals or trewe, in that one party, and by-twyne the defendent, trewe or false, in that othyr party.

A man of the King’s would fight the defendant as the means of ascertaining his innocence or guilt.

It seems that Whytehorne was certain of a guilty verdict. The outcome of the Trial by Combat would not, in itself, result in a definitive judgement of his innocence or guilt: though in the case of the latter he may well have died in the combat anyway. This point is apparently made clear to the defendant, Gregory noting that the possible outcomes were fully explained:

For in cas that the peler prevaylyd in that fyght he shulde be put in preson ayen, but he shulde fare more better than he dyd be fore tyme of fyghtynge, and be i-lowe of the kyng ij d. every [day] as longe as hit plesyd the kyng that he shulde lyf. For in prosses the kynge may by the lawe put hym to dethe, as for a man sleer, bycause that hys pelyng, fals or trewe, hathe causyd many mannys dethys, for a very trewe man schulde with yn xxiiij howrys make opyn to be knowe alle suche fals hyd thyngys of felony or treson, yf he be nott consentynge unto the same felowschyppe, undyr payne of dethe; and thys peler ys in the same cas, wherefore he moste nedys dy by very reson. Thys ys for the pelers party.

Basically, the King still had the right to determine the sentence. Though it does suggest that in the case of Whytehorne prevailing, that he ought to ‘fare better than he dyd be fore tyme of fyghtynge’.

The rules of Trial by Combat

The rules of the contest are outlined in Gregory’s Chronicle in some detail. The defendant and the representative of the King would wear ‘whyte schepys leter, bothe body, hedde, leggys, fete, face, handys, and alle.‘ They would fight with a staff of green ash. At one end of each staff a sharpened rams horn would be attached. Both the accused and the King’s man were to fast prior to the contest and could not take on food or water during their fight. It specifically notes that ‘yf they nede any drynke, they moste take hyr owne pysse’. In the event of a staff breaking the bout would continue, with the requirement that ‘they moste fyght with hyr hondys, fystys, naylys, tethe, fete, and leggys‘.

The terms of combat agreed to

bothe partys consentyde to fyght, with alle the condyscyons that long there too.

Both parties, the defendant and the alleger agreed to these conditions. In the meantime, Thomas Whytehorne asked the judge to send men to make enquiries into his good character and conduct of the people who knew him best: the inhabitants of Mylbroke [Millbrook] near Southampton.

It seems that Whytehorne’s request was agreed to. Gregory notes that inquisitions [hearings] were made on his behalf. And this seems to have failed in it’s intention as the Chronicle notes that at every place where questions were asked of his prior conduct the response was:

“Hange uppe Thome Whythorne, for he ys to stronge to fyght with Jamys Fyscher the trewe man whythe an yryn rammys horne.” And thys causyd the juge to have pytte a-pon the defendent.

The inference here is that the respondents were of the opinion that Whytehorne would suffer greatly in any such bout, so may as well simply be hanged to save him the torment. This, presumably, is why the judge has pity for his cause.

The bout begins

Gregory in his Chronicle describes the start of the Trial by Combat. Whilst it is almost certainly written for effect rather than being entrely accurate, is is of interest. The two combatants enter the area assigned for the bout from opposite sides. The defendant knelt to pray and asks every man for forgiveness. The man who he fighting disturbs this by calling him a false traitor.

The peler in hys a-rayment ande parelle whythe hys wepyn come owte of the Este syde, and the defendent owte of the Sowthe-Weste syde in hys aparayle, with hys wepyn, fulle sore wepynge, and a payre of bedys in hys hond; and he knelyd downe a-pone the erthe towarde the Este and cryde God marcy and alle the worlde, and prayde every man of forgevenys, and every man there beyng present prayde for hym. And the fals peler callyde and sayd “[t]ou fals trayter! why arte [t]ou soo longe in fals bytter be-leve?”

If Gregory is accurate, the very first blow on Whythorne broke his assailtants staff. Rather than allowing him to make a second strike with the staff the officials at the contest remove it and the two men, as agreed beforehand, were made to fight without any weapons.

The fight back

The bout, according to Gregory, lasted some time, with the King’s man gaining the upper hand. They had fought with their hands, wrestled, hurt each other across their whole bodies. And then the defendant was floored:

caste that meke innocent downe to the grownde and bote hym by the membrys, that the sely innocent cryde owt.

The result of being hit in the ‘members’ was that the defendant was now on the ground in a position that is normally rather hard to defend oneself from, let alone to attack from.

And yet, counter attack is exactly what happened.

And by happe more thenne strengythe that innocent recoveryd up on hys kneys and toke that fals peler by the nose with hys tethe and put hys thombe in hys yee, that the peler cryde owte and prayde hym of marcy, for he was fals unto God and unto hym.

He gets up on his knees, recovers, bites his opponent on the nose and gouges his eyes with his thumbs, causing cries of pain and for mercy. Which resulted in the judge ordering the combat over and the men dragged apart.

The judgement

The outcome of the Trial by Combat was that Whythorne was found not guilty, and freed. Gregory notes that he went on to become a hermit. His accuser, a Peter Sayde, on the other hand stated he hadwrongfully accusing Whythorne and other men. For this, he was hanged.

the peler sayde that he hadde accusyd hym wronge-fully and xviij men, and be-sought God of marcy and of for-gevenys. And thenn he was confessyd ande hanggyd, of whos soule God have marcy. Amen.

Notes on Trial by Combat

Trial by Combat was not common in the later medieval period. It had been used much more frequently in the Norman era. It did however remain as an option until the 19th century, with a case of Trial by Battle [of champions] taking place in 1817. Prior to that there had not been a recorded instance of Trial by Combat since 1638. Before the 1638 instance, the records of it being used as a means of administering justice are few and far between in the Stuart, Tudor, and later Plantagenet reigns.

Source of information

This particular case is written about in detail in Gregory’s Chronicle. It comes after the First Battle of St. Albans, so took place within the period we know as the Wars of the Roses.

‘Gregory’s Chronicle: 1451-1460‘, in The Historical Collections of a Citizen of London in the Fifteenth Century, ed. James Gairdner( London, 1876), British History Online

Further Reading on Trial by Combat in the Middle Ages

History the Interesting Bites – Trial by Combat.

Daily Jstor – Trial by Combat? Trial by Cake! The medieval tradition of deciding legal cases by appointing champions to fight to the death endured through 1817, unlike its tastier cousin.

Medievalists – Medieval Trial by Combat: Champions and Justice in the Middle Ages.

British History Online – Trial by Combat. Overview of legal changes and use of the method.

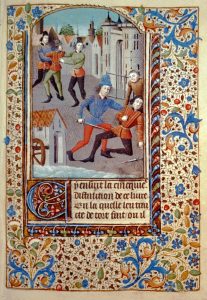

Featured Image

Mair, Paul Hector: De arte athletica I – BSB Cod.icon. 393(1 Augsburg Mitte 16. J Public Domain. Via Wikimedia.