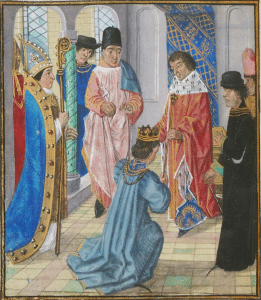

Richard II overthrown by Henry Bolingbroke, 1399

In 1399 King Richard II was overthrown by his cousin, Henry Bolingbroke. Henry’s usurpation of Richard’s Crown was the result of years of clashes between Richard II and some senior peers, known as The Lords Appellant. John of Gaunt had acted as a mediator between the Crown and the Peers. However, when John of Gaunt died his son, Henry Bolingbroke, was in exile on the continent and his inheritance set aside until such time as his punishment was served. The heir to the Duchy of Lancaster sailed back to England, landed at Ravenspur on the Yorkshire Coast, and his supporters soon had King Richard II in captivity.

Henry was proclaimed King whilst his cousin and predecessor was still alive. It was a scenario similar to that of 1327. There was an invasion, overthrowing of the reigning monarch, and the installation of a new monarch. Unlike 1327, the new monarch was not neccessarily the obvious heir to the Crown, nor was he supported by all of the peerage. Henry did, however, have enough support within the peerage and church to state his claim, have it accepted by the majority, and, despite revolts opposing his Kingship, to hold onto the Crown of England.

This post is part of a series on Kingship: Legitimacy, Rights, Traditions and Law

Henry IV’s seizure of the throne

Henry Bolingbroke did not oust his cousin, Richard II, due to the latter having no just claim to the throne. Rather, he took the throne for a variety of reasons which relate to his cousins mode and effectiveness of rule. In effect, the argument put forward by the Council of Edward III when usurping Edward II, are replicated in 1399. Richard II had, in effect, ‘ousted himself from the government of the said realm‘ and in having the backing of the church, nobles, and commons, Henry IV was accepted as King by consent and therefore right.

The Lancastrian ‘Right’ to the Crown

Henry did need to justify his position as King in terms of his right to hold the Crown. He was challenged early in his reign, with the alternatives being firstly a resoration of Richard II, and latterly through those arguing for him being replaced by a ‘rightful’ monarch, in the form of Edmund Mortimer. Politically, there were several responses to this. Clearly, rebels and those engaged in plots would be dealt with through military force, or via the enforcement of justice. The matter of ‘right’ also needed to be convincing, in order to be accepted as legitimate by the church, peers, and commons.

Henry’s justification of his ‘Right’ to be King of England

Following the death of Edward of Woodstock, the Black Prince, the matter of succession following Edward III was of importance within court and Government. Edward himself recognised this. To that end, he issued his own views on what the order of succession ought to be. Edward III’s entail was quite clear. His immediate heir was to be Richard, his grandson, as he was the rightful heir to Edward of Woodstock. In this respect, the king was simply replicating the tradition of the right of inheritance passing from eldest son to eldest son.

Further to this, Edward also noted who was next in line after Richard. This was due to his grandson being a minor. Should Richard have issue, the line would follow through that male line. This would bypass any claims based on descent from Lionel of Antwerp duke of Clarence as his heir was female. If, as became the case, Richard did not have surviving issue, Edward wrote that the next in line would be John of Gaunt duke of Lancaster, followed in turn by his eldest son, Henry Bolingbroke Earl of Derby. Note, however, that a King stating something was not ‘law‘ as such, it would still need to be agreed to by the peers, church, and commons.

In writing this, Edward III had provided a justification for Henry IV’s claim to the throne. The stated line of succession was to John of Gaunt. As the Duke of Lancaster had also died, it then passed by right to his son, Henry.

descended by right line of the blood coming from the good lord King Henry the ThirdGiven-Wilson (ed.), Parliament Rolls, viii, 25. Quoted by Mortimer, Ian in ‘Rightful Heir‘

Legitimacy was then of importance to Henry IV, either through a desire or need to be accepted. What is of note here is that whilst Edward III had indirectly provided a political justification for Henry being King, it was not those statements which were employed as his explanation of right. Instead, Henry IV opted to illustrate his lineage from an earlier monarch, Henry III. This shows a longer geneaological tie to the Crown but also side-steps any disputes surrounding the ‘right’ way of inheriting from Edward III.

Diplomacy and Henry IV’s ‘Right’ to be King

As monarch, Henry IV needed to make the case for his legitimacy. That was to satisfy or placate the commons and some nobles, and also for diplomatic reasons as his position was far from accepted internationally. The Scots referred to Henry as being the ‘duke of Lancaster [and] earl of Derby‘ [source] after his coronation, and the French were styling him as ‘Henry of Lancaster, despoiler and wrongfully ruler of the kingdom of England‘ [source] until 1407. Consequently, he had to make a case for his right to the crown.

The Lancastrian method was to address the Ten Questions that Richard II had asked of England’s lawmakers when he was challenged in the 1380’s. As a result, “The record and process of the renunciation and deposition of Richard II,” was recorded as a basis of justifying the usupation of Richard II through use of the late King’s own words. In short, the Lancastrian regime used Richard’s own arguments against him to state their right to overthrow him.

The ‘record and process‘ addresses some 33 points. They are presented as charges against King Richard II. When taken as a whole, they are similar in design to the Ordinances of 1311 and bear some similarities to Magna Carta in terms of outlining the political situation as it was at the time. As such, the ‘record and progress‘ along with previous documents provide a form of rules and/or expectations from the Barons regarding Governance by Kings. It is clear from each of these interventions by the peers of the realm that Kingship was wanted but, critically, that it had to be administered fairly in order to be just and justifiable rule. In short, the King of the day must act in a manner that has consensus backing. In other words, Kingship relies on the monarch being accepted by the peers of the realm. Or by extension, by the Estates of the Realm: the church, peers, and the commons [see Thielmann].

Richard II deposed

We procurators to all these estates and people aforesaid, … by their authority given us, and in their name, yield you up for all the estates and people aforesaid, homage liege and fealty and all the allegiance and other bonds, charges, and service that belong thereto.

Chief Justice Thirning quoted in The Right to Rule in England: Depositions and the Kingdom’s Authority, 1327-1485. Page 747. via JSTOR.

The justification for usurping Richard II was, as shown above, not based entirely on hereditary right. It was based upon the authority of ‘all the estates and people‘. That Richard could be legally overthrown was stated as fact by the Chief Justice. ‘Procurators to all these estates’ shows that the Governance of the Realm was, at least argued to be, by right of the estates acceptance of such Kingship. Effectively it states that a King has the throne by right of the estates, i.e. of the peers, people, and church. As such, they retain the right to intervene should a King not be fulfilling the promises he made within his Coronation Oath.

From John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments. Foxe’s work is an edited compilation of documents. His curation can be criticised for being rather selective in nature and is edited by himself. As such it gives an indication of what happened and how it was justified but may be coloured by Foxe’s own views.

Justification of Henry IV’s Rule: from Acts and Monuments

Whereupon, it so fel not by the blinde wheele of fortune, but by the secret hand of hym, which directeth all states: that as he beganne to forsake the maintayning of the Gospell of God, so the Lord God began to forsake him. And where the protection of God beginneth to fayle, there can lack no causes to be charged with all, whom God once geueth ouer to mans punishment. So that to me, considering the whole life and trade of this Prince, among all other causes alledged in stories against hym: none seemeth so much to be wayed of vs, or more hurtfull to him, then this forsaking of the Lord and of his worde. Although to such as list more to be certified in other causes concurring withall, many and sondrye defectes in that king may appeare in storiesMarginalia to the number of 33 articles alleged or forced rather agaynst hym.

In which, as I cannot deny, but that he was worthy of much blame: so to be displaced therfore from his regall seat, and rightfull state of the crowne, it may be thought perhaps the causes not to be so rare or so materiall in a prince, which either could or ells would haue serued: had not he geuen ouer before to serue the Lorde and hys worde, chusing rather to serue the humour of the Pope and bloudy Prelates, then to further the Lordes proceedynges in preachyng of hys woorde. And then as I sayd, howe can enemies lacke where GOD standeth not to friende? or what cause can bee so little, which is not able enough to cast downe, where the Lordes arme is shortened to sustayne? Wherfore, it is a poynte of principall wisedome in a Prince not to forget, that as he standeth alwayes in nede of God his helpyng hand: so alwayes he haue the discipline and feare of hym before his eyes, accordyng to the counsaile of the godly Kyng Dauid Psal. 2.

And thus much touching the tyme and rase of this K. Richard, with the tragicall story of his deposing. The order and maner wherof purposely I pretermitte, onely contented briefly to laye together, a fewe speciall thinges done before his fall, suche as may be sufficient in a briefe somme, both to satisfie the Reader inquisitiue of such stories, and also to forwarne other princes to beware the lyke daungers. In such as write the lyfe and Actes of this prince, thus I read of him reported, þt he was much inclined to the fauoryng and aduauncing of certain persons about him, & ruled al by their counsaell, which were th? greatly abhorred & hated in the realme: The names of whom were Rob. Weer, whō the Kyng had made Duke of Ireland, Alexander Neuile.

John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments. 1576 edition. Book Five, page 520. Link.

Deposition of Richard II: a refused inheritance?

Many narratives of the deposition of Richard II by Henry IV suggest that it was instigated by Richard refusing to allow Henry to inherit his father’s duchy and estates. This suggests that Henry was disinherited and had little choice but to take his inheritance by force, or forgo it. Research suggests that it was not as simple as this. The inheritance clearly was a matter of concern, but contemporary documents show that Henry was not denied it. Rather, the estates had been placed into a form of trust, similar to the arrangements that would be made in the event of a minor inheriting. This means that Henry would not have livery of those lands and titles immediately but at a later date. That later date, presumably, would be based upon Henry having served out time in exile and made his peace with Richard II.

This complicates matters of Henry’s usurpation of the Crown in that it suggests that Richard had been administering justice in exiling his cousin: which had happened in 1398 for a period of ten years. He would also be exercising justice and, perhaps, leniency in holding lands in trust whilst that exile was being served. In this instance it serves Henry to portray himself as an unfairly disinherited magnate, whereas the truth of the matter may be rather different. The evidence pertaining to the inheritance and how Richard II dealt with the matter is examined in this article by Christopher Fletcher.

How does the Usurpation of Richard II relate to the Wars of the Roses?

Henry IV seizing the Crown in 1399 was far from universally accepted. Plots were hatched to overthrow him before Richard II had died. The Epithany Rising sought to return Richard II to the throne. That obstacle overcome, the first of the Lancastrian Kings then faced revolts. There was warfare in Wales and the Marches from 1400 which included the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403 and led to the Tripartite Indenture of 1405. In this, Owain Glyndwr agreed with Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland and Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, to divide Wales and England between them. It would replace Henry IV with Southern England being led by Edmund Mortimer. Mortimer would have been next in line to the throne after Richard II if inheritance from Lionel of Antwerp’s daughter was accepted. The Percy Family then rose in revolt again in 1408, being defeated at Bramham Moor.

This did not end the calls for the Mortimer line to be placed on the throne. In the reign of King Henry V the Southampton Plot of 1415 sought to place Edmund Mortimer on the throne. The Southampton Plot was betrayed and saw the ringleaders executed. One of these men was Richard of Conisbrough Earl of Cambridge. The Earl was the younger brother, and heir, of the 2nd Duke of York. He was also the father of Richard Plantagenet, who later inherited his uncles Duchy to become Richard 3rd Duke of York.

When the rule of King Henry VI was challenged, it was led by Richard 3rd Duke of York. He had a line of descent to Edward III through his father via the House of York. He also had a line of descent via his mother. Anne Mortimer, wife of Richard Earl of Cambridge, was daughter of Roger Mortimer Earl of March. The ‘by right’ claim that had been presented in favour of the Earls of March was inherited by Richard 3rd Duke of York upon the death without issue of his mother’s brother, Edmund 5th Earl of March.

The arguments used against Henry IV’s right to rule therefore continued to be raised over the course of the 15th century. As Richard 3rd Duke of York came of age, the lineage used to advance previous counter-claims, were vested in him, as was the lineage via the House of York. If, as happened in 1460 resulting in the Act of Accord, the argument was to be made again, it would be in favour of Richard 3rd Duke of York being the rightful King.