Calais

Calais in the Wars of the Roses. With its fortifications, artillery, and chains to bar unwanted visitors’ access,Calais had been used as the English base for forays against France since its capture early in the Hundred Years War. The fleet based at Calais was used to patrol the English Channel, protecting merchants, and enforcing England’s dominance of the straights of Dover. This resulted in Calais and the surrounding Staple being a prized asset during the Wars of the Roses, as a base from which invasions could be launched, ideas formulated, and propaganda spread.

The Staple of Calais

The Staple of Calais was also a mainstay of the English treasury. From 1422 to 1450 it had housed a Mint, and was one way that England obtained much needed bullion:

“A petition in the parliament of December 1420 had unsuccessfully asked for the reopening of the Calais mint, supported by ‘hosting’ regulations, under which all alien merchants coming to Calais would have had to host with officially registered brokers and deposit their bullion and money with them. Foreign money and underweight English coins found on inspection would have been exchanged for new coins from the Calais mint.” Medieval merchants and money.

A similar petition was approved in late 1421 and the Mint and regulatory controls were in place by the summer of 1422.

Role of the fleet

The English fleets’ role against other nations remained important: the French were fired upon from shore-based artillery at Southampton as late as 1457 which shows how susceptible to raids the channel ports were. One of the main defences against such raids was the Calais based Fleet.

With the onset of the Wars of the Roses in England, that role was to change in some ways. However, the changes were balanced with the ever-present threat of aggression from a continental power and the ports continued role as England’s primary trading post on the European mainland.

Captain of Calais

In the years leading up to the outbreak of the Wars of the Roses the port was Captained by the Duke of Somerset, then nominally but not in reality by the Duke of York as Protector, then Somerset again, before the Earl of Warwick was handed the position following the First Battle of St. Albans. Therefore, the port was not only strategically and symbolically important but also had a history of being awarded to followers of the preeminent factions / nobles at court.

The economic problems and political turmoil of the early and mid-1450s had caused problems with regard funding the maintenance of the fortifications and the payment of the garrison. In the late 1450s this was rectified through sending customs duties raised from some ports direct to the Captain of Calais, who was the Earl of Warwick at this time. Some of the Customs levied in the Port of Kingston upon Hull, for example, directed to the Earl of Warwick for maintenance of Calais.

“Richard Anson was appointed to collect tonnage and poundage separately to hand directly to the Earl of Warwick to whom it had been assigned for expenses of keeping the sea”.

Introduction to the Customs Accounts of Hull, referring to 1458-60.

Calais in the Wars of the Roses

In 1459 the port of Calais had been heavily garrisoned. It had the only standing army maintained by the English government, some thousand plus strong well drilled men. Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick called the Calais garrison into action in England in 1459. At Ludford Bridge many of these men unexpectedly refused to fight against the King and, led by Sir Anthony Trollope, defected from the Yorkist camp to the Lancastrian one.

After the rout at Ludford and the Yorkists attainders at the Parliament of Devils, the Earl of Warwick was officially stripped of the Captaincy. In his place, the Duke of Somerset was appointed, on 9th October 1459. Somerset, however, would be forced to fight for his right to take up command.

Here we soon see the value of Calais to the Yorkists. By having possession of the port, they forced the hand of the crown. The Duke of Somerset had to attempt to oust them. Why? Because Calais not only had the 1000 strong garrison but also was home to the best fleet in the Channel. Whoever had those ships at their disposal could dominate the movement of merchant shipping, raid up and down coastlines, or transport invading armies. Additionally, it provided the holder of the port with a bargaining chip that could be used for their diplomatic gain, at the expense of their opponent.

Lancastrian attempts to seize Calais and the Staple

The Duke of Somerset landed near Calais and made attempts to seize the town and port. There, the garrison was loyal to the Earl of Warwick though, with additional men having travelled to the port in support of the Yorkists. Somerset’s Lancastrian force succeeded in taking the outlying fortress at Guisnes but was repelled when attempting to enter Calais itself.

Whilst Somerset was occupying Guisnes and awaiting additional support, the Yorkists undertook an audacious and successful raid. On 15 January 1460 Sir John Dynham raided the English port of Sandwich. Using the Calais fleet and men from the garrison they sailed across the Channel, sought out the English fleet and pounced upon it in the Haven at Sandwich. Taking the fleet by surprise, they successfully destroyed some ships, captured others, and took the Lancastrian commander, Richard Woodville, Lord Rivers, and his wife Jacquetta of Luxembourg captive.

It was a daring sea raid across the channel by a body of men who were exiled, attained and bereft of support from allies in England. That they could pull off such a feat is testament to the significance that Calais held then and throughout the Wars of the Roses.

Reaction to the Raid on Sandwich

What is notable here is that Dynham and Warwick were able to plan and orchestrate an assault on one of England’s major ports whilst the Duke of Somerset was attempting to force his way into the very port from which they set sail. The Earl of Warwick was confident enough to take a large proportion of the armed men from Calais for the mission. The force that they attacked was intended to supply and support the Duke of Somerset. The audacity of the move was astonishing, as was its success. It was worthy of note in a letter written by William Paston II to John Paston I and Thomas Playter, penned on 28th January 1460:

“As for tidings, my Lord Rivers was brought to Calais and before the lords with eight score torches, and there my Lord Salisbury reheted [berated] him, calling him knave’s son that he should be so rude to call upon him and these other lords traitors, for they shall be found the King’s true liegemen when he should be found a traitor, etc. And my Lord of Warwick reheted him and said that his father was but a squire and brought up by King Harry the Fifth, and sithen himself made by marriage and also made lord, and that it was not his part to have such language of lords being of the kings blood. And my Lord of March reheted him in likewise, and Sir Anthony was reheted for his language of all three lords in like wise.” Paston Letters

Attempts to seize the initiative: Newnham Bridge

Warwick was then confident enough to sail to Ireland to discuss plans with Richard 3rd Duke of York. It is also known that the Yorkists distributed literature along the South Coast, encouraging support for their cause at this time. Furthermore, Warwick could control what shipping was able to pass through the straights of Dover. These collectively made a Yorkist military on mainland England move viable, at a time when the Duke of Somerset remained within proximity of Calais itself.

The government attempted to send further aid to Somerset from England. Lord Audley set sail with reinforcements, but he was captured by the Yorkists. Nonetheless, Calais was vital to the Lancastrians as much as it was to the Yorkists. The Duke of Somerset made his move, despite having not received any extra men, when he learnt of the Earl of Warwick sailing [to Ireland]. The Lancastrian assault is known as the Battle of Newnham Bridge, which occurred on 23 April 1460.

Somerset’s Lancastrian force was defeated.. Calais had again showed its value to the holder. With the Yorkist leadership separated, with the Duke of York being in exile, it could have been quite difficult for a coordinated approach toward their rehabilitation being undertaken. Control of Calais and the defeat of the Duke of Somerset led to the Yorkists having a platform from which they could return, in force, to England.

Yorkist invasion of England from Calais

The Earl of Warwick returned from Ireland, shadowed but not engaged by a fleet under the Duke of Exeter. Arrangements had been made with the Duke of York for the forthcoming summer. Calais was to be pivotal in the plans. Whilst captive, Lord Audley had agreed to join with the Yorkist Lords. The Papal Ambassador, Bishop Coppini of Terrini, had preached the merits of the Yorkist cause. The Earls of March, Salisbury, and Warwick, along with Lords Audley and Fauconberg, now set sail for England.

Dominance of the English Channel allowed the 1500 strong force to sail unobstructed. The destination was again Sandwich which was taken by forces under Lord Fauconberg and Sir John Wenlock. Kent had a history of dissent against the crown and Bishop Coppini’s preaching and the exiles ability to distribute literature meant that the Yorkists gained support in the region. With a bridgehead secure and the ability to control the Thames, the Yorkists could move on London quite quickly: arriving on 2 July 1460.

Yorkist victories in England in 1460

The activities in England that followed the Calais contingent landing are well documented, as is the later arrival from Ireland of the Duke of York. The significance of Calais cannot be underestimated in these events. Had Warwick not retained the confidence of the garrison that had remained in Calais in 1459, the Yorkists would have faced huge problems. Potentially, they would have had only the Duke of York’s Irish lands to utilise as a base and little hope of preventing French aid for the Lancastrian regime.

Yorkist England and the Wool Trade

Trade, and control of it, was of huge importance to the crown following the Yorkist victories of 1461. Power was held but maintaining it required funds and a primary source of this were the customs duties collected. The main export from England at the time was wool. It was in high demand in the Low Countries, France, members of the Hanseatic League, Iberian Peninsula, and the Italian City States. As English wool was more abundant and of better quality than that available in many parts of mainland Europe, it provided the treasury with an opportunity to maximise revenues.

Economic Importance of the Calais Staple

The Partition and Bullion Ordinances of 1429 made the Calais Staple key to the control of these exports. Most wool and some other goods exported to Europe had to go through the port. The exceptions were licences granted for direct trade with the Iberian Peninsula, various agreements with the Hanseatic League, and exemption for North Eastern ports such as Newcastle to enable ease of trade with the Scots and to the far north of Europe. These Ordinances led to disputes, particularly with the Staplers of Burgundy, and, in theory at least, the export of Bullion from Burgundy to Calais was forbidden from 1454 until 1489. As many vessels carried a cargo that was not exclusively wool, it followed that those other items also went through the port of Calais.

Monitoring and levying exports

The main export port from England was London. Other ports such as Hull, Lynn, Boston, the Channel Ports and Southampton also had reasonably large volumes of wool going to Calais. The dominance of Calais as a destination meant several things:

- Quality and quantity could be checked by English officials at two ports.

- Customs duties could be applied by officials and checked. These duties were poundage and tonnage, wool custom and subsidy and petty and cloth custom (In London recorded separately, elsewhere recorded collectively).

- Payment at Calais could be regulated. And this was hugely important. It meant that demands could be imposed on payment in coin. Amid a Europe wide economic depression and a bullion shortage, this was a major factor in keeping the mints of England furnished with valuable metals with which to produce sufficient coins.

- Supply could be controlled. This was an immensely powerful bargaining tool in diplomatic talks.

An emerging merchant class based on trade through Calais

The importance of this Calais bound trade can be seen from the number of appointments made for customs officials. From 1461 to 1485 Patent and Fine Rolls record 110 appointments in London for roles associated with customs. Many of these men had also held positions at other ports, so there was a substantial professional community based around administration of customs at this time. As the value of trade via Calais was so high, the move over the period toward longevity of tenure in a customs position increased, particularly in more stable parts of the period.

The Staplers

Note that those customs officials did not actually collect duties due on wool or ‘Staple’ exports going through Calais. That was done by the Calais Staplers and it underlines the significance of their role in the English economy at the time. England’s wars and periods of economic struggle had relied very much on the grants of loans from wealthy individuals and from the wool merchants of Calais (the Staplers). The Staplers own wealth was based on the monopoly that Calais had. With the crown and the Staplers reliant upon each other’s successes, the arrangements for the funding of fortifications and ongoing garrisoning of Calais had a unique arrangement. The duties on wool were collected by the Staplers and this was used to maintain Calais’ military might. It was a system that sought to limit moments of unrest among the garrison, who had endured periods without pay, and ensured that the crown would have a ready source of loans should they be needed. Which made holding the port in the Wars of the Roses particularly important indeed as it could effectively fund any campaigning.

Monitoring the Calais Staplers

The relationship appears to have been one that at times required monitoring:

“From 1466, the London Particular Accounts of wool custom, apart from recording custom collected on wool shipped through the Straits of Marrock, were chiefly a check on the accounts rendered by the Staplers. Prominent merchants were, under this system, less likely to be attracted to the office of collector of wool customs, but the presence of a number of royal servants amongst the collectors and controllers appointed after 1466 suggests some official concern to oversee the Staplers’ activities.” The Overseas Trade of London: Exchequer Customs Accounts.

Legal actions to protect revenues

One consequence of the tight regime run by the Staplers and Crown was disgruntlement at having to pay excise duties which at times were excessively high in some quarters. This led to smuggling and instances of piracy. Some notable examples of this are noted in my general book on the Wars of the Roses – but as an overview there were 40 legal actions during the reign of Edward IV against merchants for taking Staple goods to ports other than Calais and numerous cases of merchants being tackled for failing to provide the correct assurances to officials of their intent and ability to pay the exchequer silver plate in lieu of their trade via the Staple: 14 in Hilary Term of 1463 alone, plus 5 cases of unlicensed export of coins.

Revolts and diverging views on international trade

The resurgence of warfare within England in the period 1469-71 saw Calais again become more important for its military and strategic roles. In the years leading up to the uprisings of the Earl of Warwick, there had been disagreements over where England’s continental interests lay. Warwick had pursued a pro-French line, his adversaries had preferred to adopt a pro-Burgundy line. This was complicated by the ongoing rifts between France and the Duchy of Burgundy. Both sides were fearful of an English alliance being formed with the other party. Though Margaret of York had married the Duke of Burgundy, this had not resulted in any formal alliance between Yorkist England and Burgundy. Nor had France been totally ostracised by the court. Warwick’s assumption of power in 1469 began to change that. This policy resumed upon the readeption of Henry VI.

Calais as a base for the Duke of Clarence and Earl of Warwick

When Edward IV regained his freedom from Warwick’s control the plotting continued. After the breakdown of talks to reconcile the parties, warfare erupted again. When Edward clearly had the upper hand, the Earl of Warwick and the Duke of Clarence fled to Calais. Its loyalty to the Earl of Warwick once again providing him with a strong position from which he and the Duke of Clarence could plan.

Whilst in Calais, George Duke of Clarence married Isabel Neville. This was against the wishes of his brother who had sought a diplomatic marriage for the Duke. It shows how secure the exiles felt in Calais. Warwick’s continued hold over the garrison of Calais then played a role in negotiations between the Earl, France, and Margaret of Anjou. The price that Warwick was to pay for French support in his plans for England, was the involvement of an England controlled by himself and the Lancastrian regime in campaigns against Burgundy.

The Lettres de Louis XI, roi de France

‘The only existing proofs that such an agreement was made by Warwick are the bishop of Bayeux’s letter and Warwick’s note attached to it’.

On 6 February 1471, the Earl of Warwick wrote to the Calais garrison to instruct them to engage in war against Burgundy. This was alongside the French and was designed to hinder Edward IVs potential return to England.

The bishop’s letters confirm this and hint at the extent of Warwick’s commitment to utilise Calais on an Anglo-French campaign:

‘Orders had gone forth for the assembling of a large army – and of this army Warwick himself would take command and would convey it across the sea within the time Louis had named’.

In a repeat of Warwick’s methods in 1460 the fleet was used to distribute literature in England. It noted the corruption around the court of Edward IV and the unjust rise of the Queen’s relatives. Trade to England was disrupted by the Fleets control of the channel. Calais was again proving to be a major contributor to the war in England.

Note: the above takes place as the Angers Agreement was being negotiated and put into motion.

Readeption of King Henry VI

With the successful readeption of King Henry VI, Warwick was able to pursue his preferred policy of strong ties with France. On 12 February 1471, he commissioned work to be done on forming an alliance and trade agreement with France. This followed a period of negotiations relating to trade that would marry the English to France, isolating Burgundy. The Staplers had formed an important part of these negotiations and plans. The French had courted them and other merchants with fairs and promises. The Staple was once again at the heart of political decisions. Without the support of the Staplers, Warwick, despite his dominance at court, would struggle to implement any change of policy. With its acceptance, the Anglo-French plans could proceed, and it formed part of the groundwork for the joint attacks on Burgundy that led to Charles the Bold deciding to meet Edward IV and then to support his expedition to reclaim the throne.

Second reign of King Edward IV

The second reign of Edward IV saw another shift in the practical uses of Calais. Whilst retaining its function as the main trading route into Europe, Edward had his sights on a bigger prize. It is unclear whether Edward genuinely thought that reclaiming the lost lands in France and Normandy was feasible, or whether he was simply looking for an injection of funds into the royal coffers, but once his reign was assured, he set about plotting a large campaign against France. Arrangements took some time to be finalised. Treaties had to be agreed, funding had to be secured and military planning needed to be undertaken. Calais was central to these plans.

Invasion of France

In June of 1475 Calais was to be used as the staging post for the intended joint invasion of France by the English and Burgundy. The latter failed to participate but Calais did play host to an army thought to have numbered at least 13000 men. This illustrates the size of the town and its military capacity. To hold an army of this size, plus her own garrison, is illustrative of the investment in, and purpose of Calais’ formidable defences. Dr David Grummitt has noted on the Richard III Society website that for this expedition, William Rosse, victualler of Calais was tasked commissioned to build a new artillery train for the campaign. Whilst this particular investment in artillery was intended for use on the continent, it is a reminder that the workshops of Calais were able to arm a sizeable force: both at sea, and on land.

On 5 March 1475, Edward IV ordered:

‘bombards, cannons, culverins, fowlers, serpentines and other ordnance whatsoever they be’

Armaments

Dr. Grummitt adds that from the appointment of Rosse, armament procurement was significant.

“In 1474 van Rasingham was responsible for making a great bombard, named appropriately enough The Great Edward of Calais. We don’t know the exact size of this piece and no pictures of it survive, but it cost £414 Flem. Some idea of its size, however, can be gauged when we consider that the 54 iron serpentines cast in Calais at around the same time cost £322 15s Flem. and weighed, in all, 32,275 lbs. In the opening months of 1475 Rosse received a further £2,700 from the staplers and Edward’s treasurer of war, John Elrington, with which to procure more artillery for the forthcoming ‘royal voyage into France.’ With this sum he purchased a further 45 iron serpentines and 4,000 pellets for handguns”.

Dr. D Grumitt [Source]

Treaty of Piccquigny

Even in the relative peace that followed the Treaty of Picquigny, Calais was of importance domestically and as an English tool in continental diplomacy. The crisis that took place in relation to the succession in Burgundy threatened to suck England into continental warfare. The ramifications would be great. It could impact upon the continued payment of Edward’s pension from France, whilst also reducing the influence of the House of York in Burgundy. Calais was therefore incredibly important, given its strategic location at the junction of France and the Duchy of Burgundy.

Calais and Trade 1475-1483

English trade with the continent continued to be largely via Calais following Edward IVs return to the throne. Burgundy was the chief continental ally, but the crown still needed to maximise customs duties that were collected, and the Calais Staplers remained a significant economic, and political, force.

Trade was not exclusively to Calais though. There was an increase in the number of licences granted to merchants to export to the Iberian Peninsula. Portuguese trade flourished and there was a growth in Castilian trade.

Whilst Castilian trade may not appear to be linked to Calais, it was linked to the relationships that Castile and England had with France and her allies. This meant that as England sought anti-French alliances, southern trading routes would, in communion with those to Calais, be vital to securing the materials and taxes required. The development of these mercantile links was accompanied by the ability to control other shipping routes which could hamper France’s ability to trade freely.

Safety of the Wool Fleets

The channel remained dangerous for solitary merchant vessels who were prone to attack from pirates, including English ones, and from Bretons and French at times when relations were poor. To counter this a wool fleet system was introduced. This built on earlier convoy structures that had been formalised in 1473.

“The convoy of wool fleets to Calais was similarly ancient but formalized by an agreement between Edward IV and the Staplers in February 1473 to run for sixteen years, the Staplers to be permitted once or twice a year to consult the treasurer over the provision of convoys or conduits and to retain reasonable expenses from the wool customs and subsidies they collected at Calais”. Medieval merchants and money, p172

Richard III

The strength of Calais and its inter-relationship with other ports was of significance to Richard as Duke of Gloucester and King. His royal fleet at Scarborough was supplied with victuals from Calais in 1483. Ships from merchant’s northern wine fleets were pressed into service due to the burgeoning size of connected fleets for supply and transportation of ordnance for the Scottish campaign at the end of Edward IVs reign.

Calais on the offensive

“In 1483 the unofficial war with France and the brief Anglo-Breton war had encouraged Calais patrols to vent their pent-up aggression created by the garrison’s long enforced abstinence from attacking the French during the French assault on Picardy. Two attacks in the Channel were against Lübeck and Danzig ships, the first attributed to a Captain Talbot said to be of Calais. On 20 January 1484 Luder Brames, master of le Creyer of Hamburg, en route to Zeeland had his cargo seized near Dover by John Porter of Calais, and then on the same day men of Lord Clinton assaulted him and his men, took them into custody and carried off ship and goods to Winchelsea. The master acted with dispatch and a commission dated only eleven days later ordered the mayor of Winchelsea and others to investigate”. Medieval merchants and money, p170

Calais, The Pale, and the Tudor Invasion of 1485

With the threat of invasion looming, Richard III paid part of the Adventurers of London’s conduit costs in 1484, and £350 towards their costs in February 1485.

So too was its strength of value. The Earl of Oxford was a valued prisoner, and it was felt he was more secure in Calais than within the Tower of London. Though the Earl escaped, that was due to his ability to convince gaolers to free him.

Calais posed a threat to the intended invasion of England in the name of Henry Tudor. It meant that preparations would need to be well guarded to prevent raids and the French supporters of Tudor and had the potential to engage his fleet once it set sail.

Richard appointed his illegitimate son, John of Pontefract, as Captain of Calais, presumably with ensuring the loyalty of the garrison in mind.

Further Reading and Sources of Information

Grummitt, David. The Calais Garrison: War and Military Service in England, 1436-1558 (Warfare in History)

Medieval merchants and money: Essays in honour of James L. Bolton Edited by Martin Allen and Matthew Davies.

Childs, Wendy R. Anglo-Castilian Trade in the Middle Ages.

‘Introduction’, in The Overseas Trade of London: Exchequer Customs Accounts, 1480-1, ed. H S Cobb (London, 1990), pp. xi-xlvii. British History Online [accessed 12 March 2021].

Moorhouse, Dan. On this day in the Wars of the Roses

Santiuste, David. Edward IV and the Wars of the Roses. Chapter 2: Calais.

Unnamed author. The Outbreak of War between England and Burgundy in February 1471. Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, Volume 33, Issue 87, May 1960, Pages 114–115,

Grummitt, David. “The Defence of Calais and the Development of Gunpowder Weaponry in England in the Late Fifteenth Century.” War in History, vol. 7, no. 3, 2000, pp. 253–272. JSTOR, . Accessed 11 Mar. 2021.

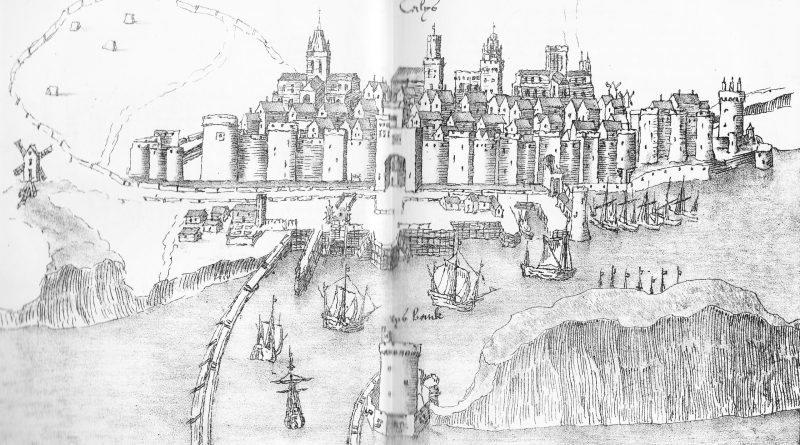

Featured Image

Calais. From The Chronicle of Calais in the Reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII