York in the Wars of the Roses

York in the Wars of the Roses was not a particularly Yorkist City. The Civic Authorities within the City of York were, in general, loyal to whomever held the crown at any given time. The City professed its loyalties to the Houses of Lancaster, then York, and upon the Tudor victory reiterated its bonds to Henry Tudor‘s Lancastrian kin. The City of York is, however, closely linked to King Richard III through his time as Edward IV‘s lord of the north and York’s role in the governance of lands north of the Trent. York’s history during the Wars of the Roses is complex and illustrates the difficulties faced by municipalities when faced with political change and violence on a national scale.

The role of York in the Wars of the Roses forms a significant part of my book on Betrayal in the Wars of the Roses. This explores the bonds that an urban area owes to the crown, local magnates, its citizens, and the merchants upon whom the area relies for economic wellbeing. It is a fasinating if complex series of loyalties, rights, and responsibilities that are only equalled by the issues faced by London and Westminster, with other major townships having similar dilemmas without neccessarily having the same level of regional and national significance.

Governance of York to 1461

The City of York was administrated by a City Council with a Mayor and Aldermen elected by the citizens. The electorate was small. It was largely centred around merchants of the city. This council was responsible for day to day governance of the City, incorporating things such as the defence of York, justice within the ciy and Ainsty, poor relief, and matters such as public health. By the standards of the day, York was quite large. In the period of the Wars of the Roses it was England’s second city. York had close bonds with the church: though the two had separate administrations on most matters. Regionally, the city had significant roles. It was at York that many of the more serious crimes from the Ridings of Yorkshire would be tried. Here too was where arrays would take place for campaigns against Scotland. This all meant that the urban authorities had a complex relationship with the church, crown, local magnates and merchants from home and abroad. For the City authorities, their primary role was the wellbeing of York, with economic prosperity at the forefront of this.

York – a Lancastrian Capital at the heart of Yorkshire

As the Wars of the Roses burst into life, the City of York found itself as home, albeit briefly, to the Lancastrian court. It may seem a little strange that York was effectively a Lancastrian Capital, but that is precisely what the scenario was in 1460-61. Following the Act of Accord the nobility loyal to Margaret of Anjou gathered in several key locations. One was based around Lancastrian lands in the Midlands. This powerbase saw forces act against Yorkists in 1459, at Blore Heath, and saw Parliament being held in Coventry (the Parliament of Devils) in which the Yorkist lords were attained. Following that, the Lancastrians were pushed to the safety of the north. King Henry VI was taken into Yorkist hands at the Battle of Northampton. The Yorkists were able to force the Act of Accord through a partisan parliament. And the response of Queen Margaret was to move herself and the Lancastrian court to York.

Lancastrian Lords in Yorkshire

The Lancastrians enjoyed regional support in and around York. Contrary to some misconceptions, the County of Yorkshire had many lords who owed their allegiance to the House of Lancaster. Chief among these was the Earl of Northumberland, who was also influential over the region. To the South, the Aire Valley was largely held by Lancastrian nobles, making York a relatively safe haven as they controlled the relatively few places at which a sizeable force could cross the river. York was a logical choice in that respect as it also restricted movement of Neville retainers intending to travel south to join with the main Yorkist armies.

York as a logical base for Lancastrian loyalists

As a venue of choice for the Lancastrian regime, the City of York itself had little option but to accomodate and supply the Queen and her supporters. As indepedent as the city authorities were, they were also bound by simple pragmatism, and a duty to the people of the city. Hosting the Lancastrian army as it grew in size was not particularly a sign of tactit support for them, equally it was not a sign of the Mayor and Aldermen having any form of view on the Yorkists, or Parliamentary matters.

It was from York that Margaret of Anjou travelled to Scotland to seek military assistance. It was also to York that forces travelled from around the country. Actions by Lancastrian forces based in York began earlier than a reader may expect. Orders were issued by the Yorkist government in London from July 1460 onwards in respect of ‘oppressors, plunderers, and slayer’s of the kings people in Yorkshire‘ [Pollard, North Eastern England during the Wars of the Roses. p279]. It was met with derision by Lancastrian nobles based in York and nearby strongholds. Looting of manors held by the Duke of York and Earls of Salisbury and Warwick near York took place, with an escalation of attacks following news of the Act of Accord in October 1460 [Calendar of Patent Rolle 1452-61, p651].

War approaches: York as a staging post

York then acted as a staging post. As Richard 3rd Duke of York headed north, the Lancastrian army made its way to Sandal Castle, Wakefield. At Sandal, through luck or trickery, they met the Yorkists on the ground outside of Sandal Castle. The Battle of Wakefield was a major Lancastrian victory. It resulted in the death of Richard 3rd Duke of York, the capture [then execution at Pontefract] of the Earl of Salisbury, and the death in the rout of the Earl of Rutland. The heads of the Duke of York and the two Earls were taken to the City of York, where they were displayed on pikes above Mickelgate Bar.

Queen Margaret returned to York from Scotland after the Battle of Wakefield had taken place. It was at York that she called a Council which decided upon a course of action aimed at retrieving King Henry VI from Yorkist custody. In simple terms the Council decided to go on the offensive. York subsequently became a place of array and site to which a large armies supplies were organised [source]. The resulting campaign saw the Lancastrian army march south. A force commanded by Sir Edward Poynings was attacked at Dunstable [source]. Thereafter the Lancastrians marched to St. Albans, defeating the Earl of Warwick’s force. It then marched on London before opting to return to York.

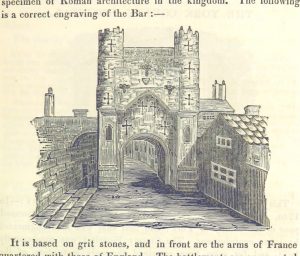

The New Guide for Strangers and Residents in the City of York … [By William Hargrove.] From Picryl

York under Yorkist Rule [1461-69]

Fyrst, oure Soverayn Lord hath wonne the feld, and uppon the Munday next after Palmesunday, he was resseved in to York with gret solempnyte and processyons. And the Mair and Comons of the said cite mad ther menys to have grace be Lord Montagu and Lord Barenars, whiche be for the Kyngs coming in to the said cite desyred hym of grace for the said cite, whiche graunted hem grace.

Paston Letters 4 April 1461

Despite having played host to King Henry VI, Queen Margaret, and Prince Edward in the days before the Battle of Towton, the City of York welcomed Edward as King of England once he had secured victory. As noted above, this does not neccessarily mean that the Mayor, Aldermen, or people of York were supportive of his cause over that of the Lancastrians. It is simple pragmatism to accept the victor and treat him graciously. Especially when there is a large, victorious, army behind him.

Yorkist base in the North

The Yorkists used the City of York as a headquarters from which they attempted to oust Lancastrians resisting in the north. It was from York that nobles and the gentry were commissioned to take control of key towns: Hull and Scarborough, for example, were priorities. So too were men assembled at York for the task of taking castles in the North East. This tied in with forces and ordnance being shipped to the north, using the ports of Hull and Newcastle as points of disembarkation depending on the military objective.

Campaigns in the North

The role of York was of huge importance to King Edward IV in the early part of his reign. In 1463 the Scots attacked Norham Castle in Northumberland. It was a sizeable and alarming assault, instigated by Queen Margaret and Queen Mary (of Guelders, Regent and Dowager Queen of Scotland). It resulted in the Earl of Warwick, then based at Middleham Castle, calling for military and financial aid. Consequently a tax was levied for an invasion of Scotland. The army was due to meet at Newcastle in September 1463. The King travelled to York in preparation for the campaign. That campaign never took place, but the King remained in York for four months.

Political and Diplomatic centre

Parliament was initially summoned to sit in York in February of 1463 [it dodn’t, it was transferred to Leicester and later to Westminster]. Notwithstanding the alteration of Parliament, York played a major role in governance at the time. Diplomatically it was to York that Scottish envoys travelled in 1464 to agree a truce, then treaty, with England. It was an attempt to block the escort for these envoys by Lancastrians that led to their defeat at the Battle of Hexham. Following the Battle of Hexham a number of Lancastrians were taken to York, where they were tried and executed as traitors [source].

Defences improved

The importance of York to the new regime is reflected in actions by the Mayor and Aldermen of the city. In April 1463 additional measures were taken regarding the defence of the city:

two tall watchmen at each barr and their duty. It is agreed that from henceforth every barr shall be dayly kept with two tall men unarrayed to the intent that if any suspected person comes in at any of the said barrs they may have knowledge of them and be ascertained of the cause of their coming and whence they come and whither they purpose.

4 men of the ward to watch each night….

barrs to be shut at 9 at night and opened at 4 in the morning… and the keys nightly be brought into the mayor’s keeping.

29 April 1463. City of York Records. York House Books, page 690

Prepared for war

For context, 4 men in each ward was a war footing. It equates to more men on guard than were arrayed by the city to fight for Richard III in 1485, for example. It also follows previous upgrades in the watch, for example the city increased the watch in November 1461 [f.8 York House Books, p689] Other orders by the civic authorities make the military importance of York clear. For example, on 18 July [year unclear but 1463 or 1464 seems likely] orders were given regarding the walls and its guns:

The gunns of the city to be reparelled, gunpowder bought and that the walls of this city shall be overseen and the defaults of them amended by the oversight of the wardens of the walls.

18 July [unclear year]. City of York Records. York House Books, page 690.

Revolts, Readeption, Return of the Yorkists

1469 saw a revolt break out in the name of Robin of Redesdale. Tied to the actions of the Earl of Warwick and Duke of Clarence from Calais and in the south, it posed a large risk to King Edward IV and to the City of York. Though likely exaggerated in terms of numbers of rebels, this entry illustrates the threat to York:

There were no less than 15,000 men assembled, who marched with one Robert Huldurn at their head direct for York. But the Marquis of Montague being informed of their design, went out of the city with a few troops, and attacking them, when they least expected it, put them to the rout, took their leader, and caused his head to be cut off.

Rapin’s Acta Regia, p. 285

1470: England invaded, Edward IV flees to Flanders

This was followed by King Edward IV basing himself in York in 1470. His stay in York coincided with the force of the Duke of Clarence and Earl of Warwick landing on the south coast [source]. Edward’s time in York was spurred in part by the Lincolnshire rebellion that occured in spring of 1470, along with concerns of another revolt from men loyal to the Earl of Warwick in North Yorkshire. Once again the City of York demonstrated its strategic importance to the crown. With a supportive council, mayor and aldermen, along with regional magnates who were, at this time, supportive of his rule, York was a natural choice as a base from which to counter a variety of threats.

From Ravenspur to York: Return of Edward IV

The year after, Edward IV returned. He landed at Ravenspur on the Yorkshire coast. From here, he made his way to York. Edward’s reception by the city was one that reflects the priorities of an urban authority. They politely declined to admit him as King, as any further reversal in his fortunes may reflect upon them with consequences. Instead, they allowed him and a number of his followers to enter based upon his right to the title of Duke of York. The following passage, from Arrivall which was written at Edward IV’s request, illustrates the dilemma faced by the city authorities:

wherfore the Kynge, keping furthe his way, cam beforn Yorke, Monday the xviij. day of the same monithe. Trewthe it is that aforne the Kynge came at the citie, by iij myles, came unto him one callyd Thomas Coniers, Recordar of the citie, whiche had not bene afore that named trwe to the Kyngs partie. He tolde hym that it was not good for hym to come to the citie, for eyther he shuld not be suffred to enter, or els, in caas he enteryd, he was lost, and undone, and all his. The Kynge, seeing so fer∣forthly he was in his iorney that in no wyse he might goo backe with that he had begone, and that no good myght folowe but only of hardies, decreed in hymselfe constantly to purswe that he had begon, and rathar to abyde what God and good fortune woulde gyve hym, thowghe it were to hym uncertayne, rathar than by laches, or defaulte of curage, to susteyne reprooche, that of lyklihode therby shulde have ensued; And so, therfore, notwithstondynge the discoraginge words of the Recordar, which had be afore suspecte to hym and his partie, he kept boldely forthe his iorney, streyght towards the citie. And, within a while, came to hym, owt of the citie, Robart Clifford and Richard Burghe, whiche gave hym and his felowshipe bettar comforte, affirmyng, that in the qwarell aforesayde of his father the Duke of Yorke, he shuld be receyvyd and sufferyd to passe; whereby, better somewhate encoragyd, he kepte his waye; nathcles efte sonnes cam the sayde Coniers, and put hym in lyke discomforte as afore. And so, sometyme comfortyd and sometyme discomfortyd, he came to the gates afore the citie, where his felashipe made a stoppe, and himself and xvj or xvij persons, in the ledinge of the sayde Clifford and Richard Burgh, passed even in at the gates, and came to the worshipfull folks whiche were assembled a little within the gates, and shewed them th’entent and purpos of his comming, in suche forme, and with such maner langage, that the people contentyd them therwithe, and so receyvyd hym, and all his felawshipe, that night, when he and all his feloshipe abode and were refreshed well to they had dyned on the morne, and than departed out of the cite to Tadcastar, a towne of th’Erls of Northumbarland, x mile sowth∣wards.

Historie of the arrivall of Edward IV. in England and the finall recouerye of his kingdomes from Henry VI. A.D. M.CCCC.LXXI. / Ed. by John Bruce. Page 5

An unbiased approach to national turmoil?

In effect the City of York was forced to play politics. The diplomatic solution was to admit Edward by right of his claim to the title of Duke, but not as King. This is because the city and region had mixed affinities. Edward IV had for his part chosen to make his way from the coast to York through Percy held lands. In contrast, there were forcces under the Marquess of Montagu and Neville retainers in Richmondshire who were supportive of Edward’s opponents. Recognising that there was a potential pitfall through any semblance of partisan support for either side in the conflict, York opted for a safety first policy. In short, its loyalty lay with its citizens and averting any potential for unrest or violence in and around the city was in their best interests.

York and Richard Duke of Gloucester’s dominance of the North

From 1471 until his death in the Battle of Bosworth, Richard duke of Gloucester, then King, had a close bond with York and the North of England. Whilst many of these ties are away from York, primarily at Middleham, his links are clear and of note.

Throughout the period of Richard’s influence, the City of York remained an independent urban authority. It retained its own structures for justice and administration. However, it also became home to some of the systems that were put in place: particularly as King, when Richard created the Council of the North which was based in the city.

Lord of the North

An agreement with the earl of Northumberland in 1474 ensured his dominance and effectively made other northern lords his servants.

Whilst this agreement did not explicitly reference the City of York, or any obligations to or from the authorities there, it placed Richard as de facto leader in the North. As a consequence the Mayor and Aldermen of York were increasingly reliant upon the goodwill and support of the Duke of Gloucester. His overlordship in the region now meant that to get things done regionally, or promoted nationally, may need to go through Richard and have his support. This is evident in communications on matters such as Fishgarths and upholding of the law. [Richard intervened regarding Fishgarths on several occasions: see City of York Records. York House Books pages 10, 128, 130 and 312]

Patronage to and from York

Richard’s ties as Duke of Gloucester stem from two way patronage and use of his influence for the betterment of York. They also stem from commands issued by King Edward IV in respect of the roles that he gave to the Duke of Gloucester and Earl of Northumberland in respect of the City of York. In this case, it shows that the Crown was willing to overrule the independence of the urban authorities by granting magnates rights that could supercede those of the local justices:

13 March 1476

The king our sovereine lorde straitely chargith and commaundith that nomanere man of what so evere condicion or degree he be of, make ne cause to be made any affray or any othir thing attempt or doo, wherthrough the pease of the king our said sovereign lorde shulde be broken; nor that no man make nor pike any quarrell for any old rancour, malice, matier or cause hertofore donee….

And overe this the right high and mighti Prince Richard duc of Gloucestre, great constable and admirall of England, and the right noble Lorde Herry erle of Northumberland on the kinges behaulf straitely chargeth and commaundith that every man observe…

f.2v City of York Records. York House Books. Page 8

Roles for Richard Duke of Gloucester and Henry Earl of Northumberland in York

This role came without any particular title for either the Duke or Earl. It was the king simply stating that the two senior magnates could act on his behalf to ensure the rule of law within the City of York. As such the urban authorities increasingly notified the Duke of Gloucester of matters pertaining to justice. He was asked his opinions and kept up to date with outcomes. This is shown several months after the above proclamation was distributed in York. A serious charge was laid against Thomas Yotten of York. The city notified the duke of Gloucester whilst he was in residence at Middleham Castle. Richard replied on 8 July 1476. asking the City to ‘occupie the saide office according to thayre liberties, grauntes, privalages…‘. The city council responded on 19 July agreeing that a response [to Yotten] should be drawn up under common seal, with copies to the duke of Gloucester and the lords Hastings and Stanley. [City of York Records. York House Books p51]

Political structures, systems, and patronage

Similar examples can be found throughout Richard’s time as Duke of Gloucester. His interest in, and the cities duty to inform him, continued as he was Lord Protector, and as King of England. This was made more official through Richard being created Lieutenant General of the North, which gave him oversight on all matters whilst actually being a military role. As King Richard then created the Council of the North which bound the City of York, and all major towns in the region, to the Crown more formally: a structure that continued throughout the Tudor dynasties rule over England.

Anti-Richard dissent

Of course, not everybody was happy with the influence that Richard had over the City of York. Whilst much of the documentation shows what is essentially good lordship and respecful correspondence in both directions, there was dissent aimed at the duke in relation to his roles in the north. One such example is the Slander charge made against Master William Melrig in June 1482. He was reported as having been heard saying:

What myght he do for the cite? Nothing buy gyrn of us.

Master William Melrig cited as slandering the duke of Gloucester. 24 June 1482. City of York Records. York House Books p696

City of York taxes and tolls

Regardless of the occasional word of dissent against the duke of Gloucester, the bond he had with the city authorities remained a close one. As Lord Protector he was approached by the City with regards the level of taxation upon the people of York.

…your worshipfull citie remanyth in poverte, for which ye desir us to be good mean unto the kynges grace for ane ese of such chargez as ye yerly bere and pay unto his (grace) highnesse, we lat you wit that for such gret materes and bysynessez as we now have to do for the wele and usefullnes of this realm… as as yit ne can have convenient leyser to accomplysh this your busnes, but can be assured that for your kynd and luffyng disposicions to us at all tymes shewid which we ne can forget, we in gudly hast schall so indevour us for your ease in this behalve as that ye shall varaly understond we be your especialle gude and lovyng lord…

14 June 1483. City of York Records. York House Books p712

York’s role as Richard became King of England

The events of summer 1483 saw the City of York being asked to assist Richard as Lord Protector. City records show a flurry of communications and debates in the city regarding assistance that they had been asked to provide. 15 June 1483 saw a decision to send:

Thomas Wrangwysh, William Welles, Robert Hancock, John Hag, Ricardus Marston and William White with CC horsemen defensably arrayed shall ryd upp to London to asyst my said lord good grace and to be at pomfret at Wedynsday at nyght net coming

On the following day further men were assigned for the duke of Gloucester, incorporating men of the Ainsty. 17 June 1483 then saw the Mayor and Aldermen making provision for the payment of men arrayed for service in London under the Duke of Gloucester. Even when the summonses to Parliament were cancelled, the response of the authorities in York was to continue planning for military assistance for Richard Duke of Gloucester.

thys notwythstanding it is agreid that the said ThomasWrangwysh and William Welles shalbe captens of the soghers for the said cite

City of York Records. York House Books p285

Benefits from Richard III’s kingship

The ties with York remained close following Richard becoming King. York was one of the locations that benefitted from interventions by Richard regarding toll payments. Whilst this is not neccessarily due to close links: such eemptions were often granted to towns facing economic problem, it is illustrative of the way in which the City of York worked with the Crown during Richard’s reign. [On 17 September 1483 Richard III relieved the City of York of its tolls. City of York Records. York House Books p729] This exemption was granted whilst Richard was resident in York as part of his progress as King. He also responded, on 19 September 1483, to complaints from weavers in the City of York about weavers in the Ainsty not paying the same levies. Richard asked the sheriffs to ‘geve unto them your lawful favor and assistences at alle tymes as the caas shall require’. City of York Records. York House Books p733

1485 – York, a City of divided loyalties?

1485 saw the city requested to array men for defence of England against the likely invasion of Henry Tudor. In July the authorities began preparations for their role in the forthcoming campaigns:

evere man of any craft within this citie forsaid being ffranchest be redie defensibly areyed to attend upon the mayre of this citie and his brether for saveguard of the same to the kings behove or otherways at his commandment.”

Attred, Lorraine. York House Books 1461-1490. Volume One. p. 366.

In August, news of Henry Tudor landing was communicated to the City. On 19 August the Mayor and Aldermen made arrangements for a deployment to be sent to Richard III’s aid:

…iijˣˣ menn of the citie defensible araiyed, John Hastinges gentilman to the mase being capitayn, shuld in al hast possible depart towardes the kinges grace for for the subduying of his ennemyes forsaid…

Attred, Lorraine. York House Books 1461-1490. Volume One. p. 368.

The men arrayed for Richard III’s army did depart for Nottingham. As they were on their way the King marched to Leicester, then to Bosworth where on 22 August 1485 he met the Tudor army in battle. News of the defeat reached the City of York quickly. Official letters dated 23 August to the Earl of Northumberland refer to the battle.

York’s response to the death of Richard III and beginning of the Tudor era is intriguing. It is the subject of discussion in my book on Betrayal in the Wars of the Roses.

1487: Lambert Simnel’s Invasion

1487: City of York. Supplying an army whilst keeping the peace

Medieval York: Links and References

British History Online. An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 2, the Defences

History of York – Medieval York

Yorkshire Museum – Medieval York – Capital of the North

Oxford Bibliographies – Medieval York

Richard Duke of Gloucester / Richard III and the City of York, or the North

De Re Militari – Richard Duke of Gloucester Lord of the North

National Archives – Becoming Lord of the North, 1452–1483

Oxford Reference – The Council of the North

Richard III Society – The North

Richard III Rumour and Reality – The Council of the North

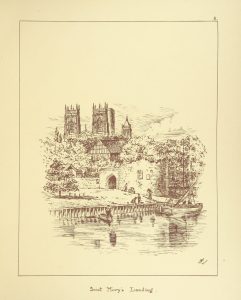

Featured Image

York Minster. Title in Detroit Publishing Co., Catalogue J foreign section, Detroit, Mich. : Detroit Publishing Company, 1905: “Great Britain and Ireland. York. Minster. S.W.” Print no. “10460.” Also known as Cathedral and Metropolitical Church of Saint Peter in York. Via Pictryl.